The seventh child in a Dutch Reformed family, I was born midway the Second World War – precisely one year before D-day – in The Hague. I had six siblings: two sisters, four brothers. Three weeks after my birth, the family moved to Amersfoort because food was becoming scarce in The Hague. Yet also in Amersfoort the final two war years were stormy times. Our back yard became a vegetable plot and my oldest brothers had to go into hiding to escape forced labor in Germany. I was sitting on my Dad’s arm to watch the Canadian armed forces enter town and liberate us. Back to The Hague. My father worked for Royal Dutch Shell and we found a new home in the sleepy, green neighborhood called Benoordenhout, just across from the wooded Clingendael estate where today the like-named think tank finds its home.

I remember my early years, growing up in our large family, as wonderful and without any worry in the world. Our home was a lively place that could become chaotic, yet was always a warm nest. My grandmother was living with us and she would read me stories from Rip van Winkle that were beautifully and fairy-like illustrated by Arthur Rackham, or from Lagerlöf’s Nils Holgersson. After my older sisters and brothers had left home, life slowed down and the relationship between my parents and me intensified.

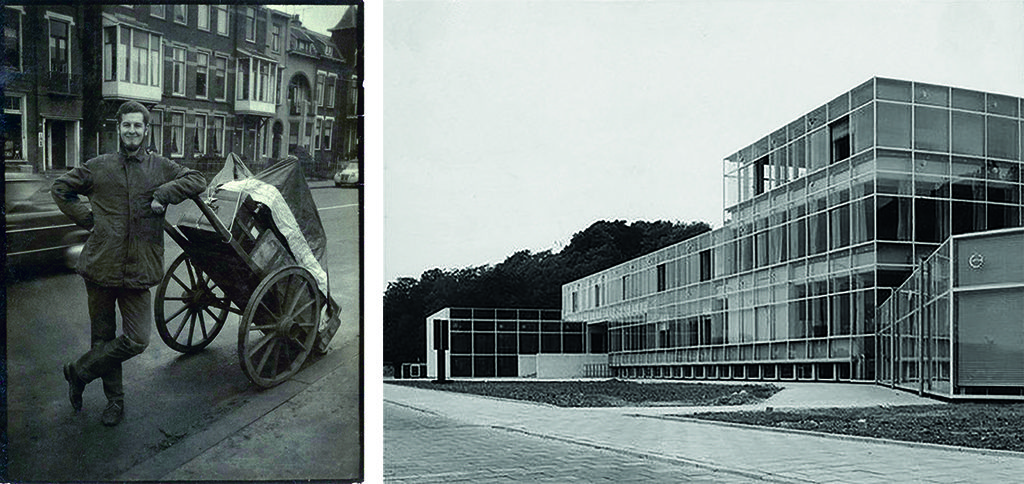

I have always been busy at creating things and sketching. I attended Christelijk Lyceum Zandvliet where my art teacher was the later comedian Paul van Vliet’s father, an inspiring man. My highest marks were for art. Although my mother had a past career as fashion design teacher and was not only an expert illustrator but an accomplished piano player as well, my parents didn’t line out a creative future for me. On the advice of a free-thinking uncle, only hesitantly supported by my worried parents, I applied for enrollment at the art and crafts academy, the one in Arnhem. This academy had a certain fame for its quality education of the applied arts such as fashion design, graphic design and 3D design, fields that prepared students for a future career in industry, which was what my parents thought was best for me. Having successfully passed three days of entrance exams, I started my education in September 1961: day school at the publicity design and graphic design department.

Harry Verburg was the academy’s director who, trying to get rid of the Arnhem academy’s regional image, had attracted new teachers from Amsterdam and especially from The Hague. The typographer Jan Vermeulen, the graphic designer Bob Balke and the industrial designer Marius Wagner were my most important teaching professionals. The discussions with and lectures and tasks received from Wagner especially were of great influence. They introduced me to the young profession of industrial design, and I decided to attend industrial design class, preferably at the Hochschule für Gestaltung (HfG) in Ulm, Germany. This Bauhaus successor proudly presented teachers like Max Bill, himself a former Bauhaus student. Yet, HfG’s social critique was not acceptable, thought the ultra-conservative Baden-Württemberg state government. Confronted by an unsolvable dilemma, after fierce debates HfG decided to close HfG Ulm.

Wagner told me of the three-year study course of industrial design at KABK he himself had taken at the royal academy of art in The Hague, the first of its kind in the Netherlands. In October 1968 a new three-year cycle was about to begin and I hurried to join. The department’s teachers were renowned professionals such as Kho Liang Ie, Willem Rietveld and Friso Kramer. Classes took place on Fridays and Saturdays, and combining these with freelance projects for The Hague advertising agencies, studying, making mock-ups and drawings, and joining study trips to studios and factories wasn’t easy.

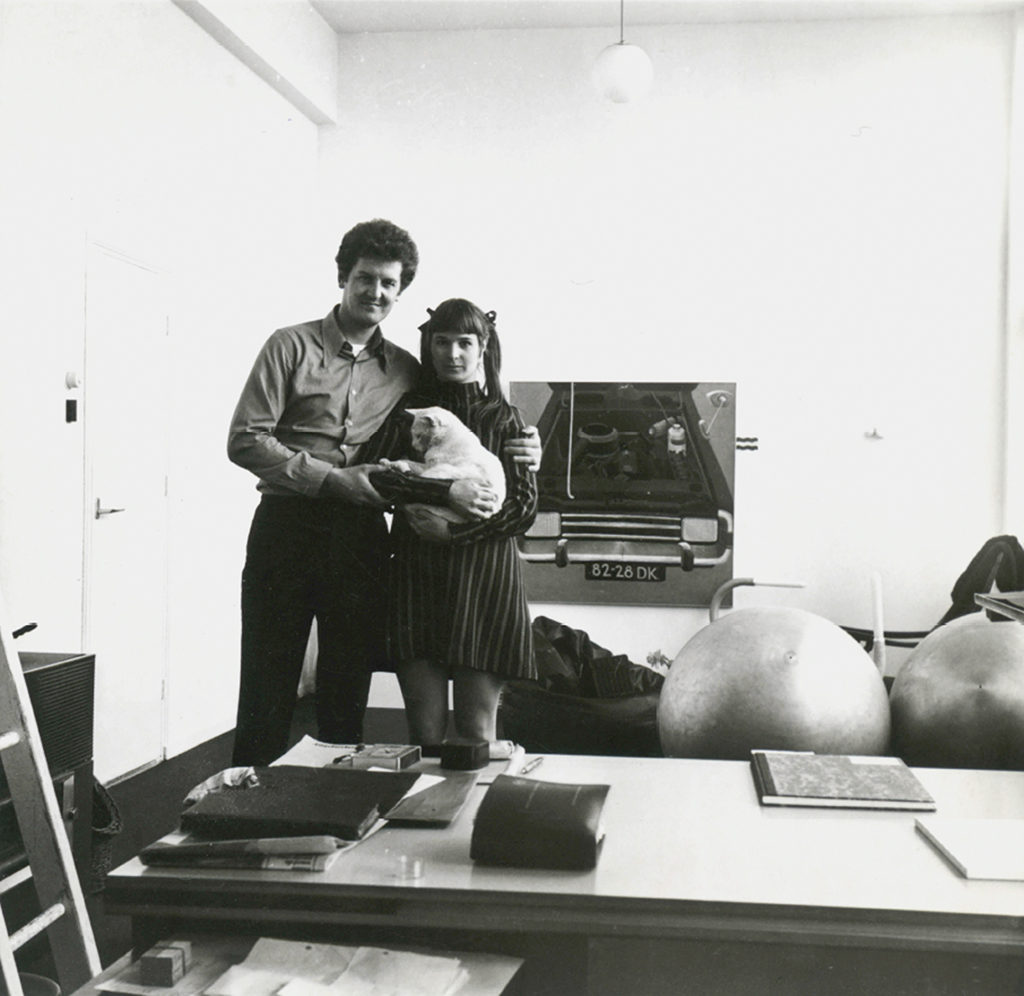

In 1964, Arja van den Berg had entered the Arnhem academy to study art. Her combined shyness and pureness touched me deeply. A beautiful girl – and I found myself to be hooked. I told my friend Erno Dieruff that I wanted to marry this girl even if I didn’t really know her yet. Five years later, Arja graduated and was awarded the Teachers’ Prize, and it took less than a year before we had gotten married, now fifty years ago. In 1971, it was during one of the last of my classes in The Hague, Kho Liang Ie asked me to join his studio staff. A real job and paid too! Arja and I spent many hours discussing this opportunity and in the end I called Kho to tell him I’d rather be independent.

In later years, in professionally hard times, I often thought of that bold decision. Yet, in 1969, my membership application had been accepted by GVN, the professional organization of graphic designers (with Jurriaan Schrofer in the ballot commission); a year later I had joined KIO, the circle of Dutch industrial designers. I expected much of my newly acquired professional status. We had to live frugally, stayed illegally in an apartment in one of the newer suburbs of The Hague, Moerwijk, one floor below the painter Rein Draayer’s studio, but our poverty never prevented us from buying important magazines such as Abitare, Domus, Formor Gebrauchsgraphik as well as the trendy German magazine Twen, and other publications that introduced us to the international design and architecture avant-garde: Studio Alchimia, Alessandro Mendini, Memphis, Dieter Rams and Ettore Sottsass (whom I met later in Rotterdam). Domus especially was an important source of inspiration not just for me, but surely for many other European architects and designers.

In The Hague, I had connected to Checkpoint, a design collective attracting creative people from a diversity of professions: photographers, filmmakers, interior and fashion designers, and artists. I felt much at home in the dynamic environment they’d created. I befriended the graphic designer Rien Hagen and, in 1970, together with kinetic artist Ray Staakman and utopist Alfred Eikelenboom, I as a graphic and industrial designer became a subject in a Rien Hagen and Ton Hasebos documentary film for VPRO television. Producing the film was a joy, the scenes and images were surprising but, alas, they didn’t attract any new clients and design commissions.

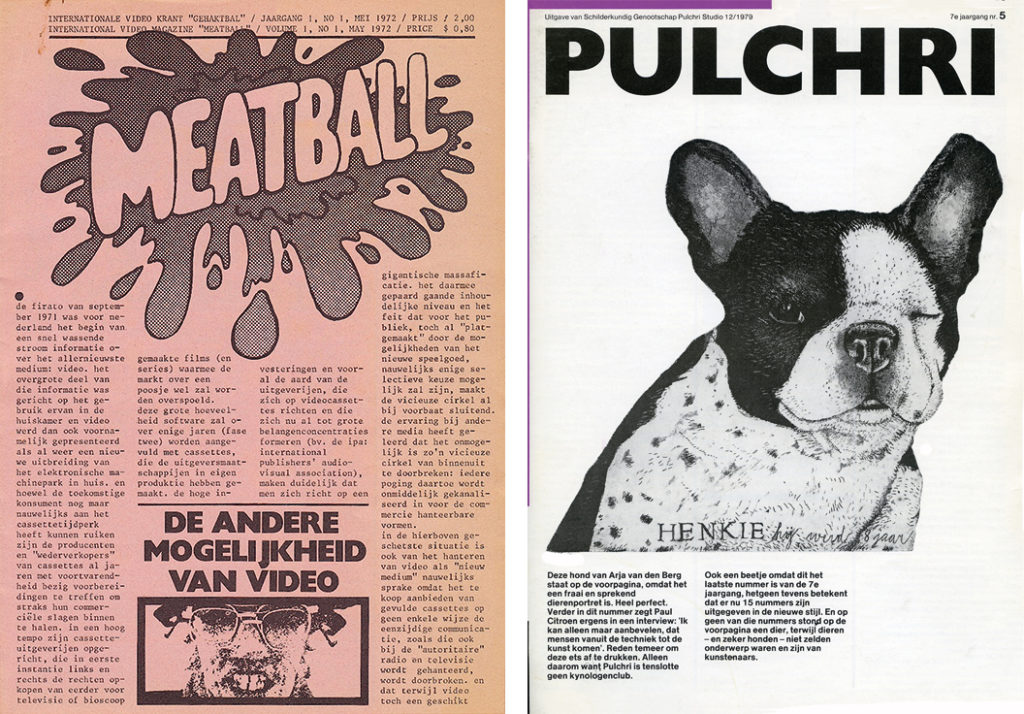

Our experiments with the then new medium video caught the attention, though, of Wim Beeren who, as the director/curator of the big sculpture, installation and new media event Sonsbeek buiten de perken (1971), commissioned Rien and me to create a video report of this unique exhibition centered in Arnhem but extending all over the country. A year later, this project brought us, together with the publisher Paul Brand and Loek van der Sande, later of Total Design, to create the video workgroup Meatball (named after a Robert Crump cartoon character). In a recent interview with Koos Slootweg, Rien Hagen correctly recalled: “As children of our time, we were anti much if not everything and had a strong sense of social responsibility. By using video we wanted to give the people a voice.” I designed Meatball’s logo, their identity program and unique magazine and, later, film posters for The Hague’s independent movie house, Het Kijkhuis. I remained a Meatball board member until early in the 1980s, although I was becoming aware of a stronger affiliation with my own profession.

In 1976, GVN asked candidates to apply for the design of traveling exhibition about sign posting. I was interested in the subject and sent in a proposal. I got the job! The complicated project, called Linksaf, rechtsaf, alsmaar rechtdoor (Left turn, right turn, continue straight ahead)was realized with the help of many GVN members. Paul Mijksenaar and Arthur Eger were the project managers and wrote the texts. Paul and I, accompanied by our partners, took the exhibition to London, where it was presented at the Royal College of Art. Herbert Spencer showed us around.

Jurjen de Haan, the newly elected chair of The Hague’s artists’ society Pulchri Studio, asked me to restyle their until then mimeographed bulletin. Together with the art historian John Sillevis and the writer Ton Haak I designed an A4 format magazine with a clear lay-out and the use of lots of images; after 42 years the magazine,Pulchri, is still being published four times a year, now in full color.

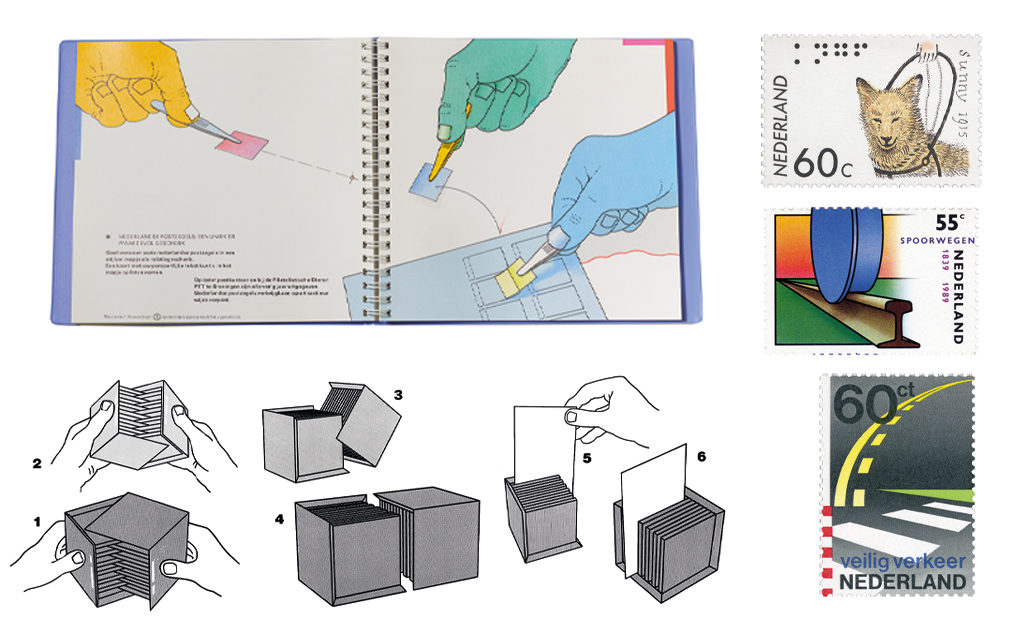

The Dutch PTT’s esthetic design department (DEV) also existed for 42 years, from 1945 to 1987. They were important clients and promotors of many a young artists and designers, me included. With their critical approach to all projects and their high quality standards they were an exciting and stimulating client; they were open to almost everything. Working for DEV was a recommendation for other clients. In the 1970s and 1980s I worked on several projects with DEV’s Paul Hefting, Henk Gilhuis and Ewoud Bezemer and it was always an enjoyable collaboration. I designed new counters for post offices; shelters and interiors for mobile post offices; postage stamps and much more, as well as illustrations for PTT calendars, etc.

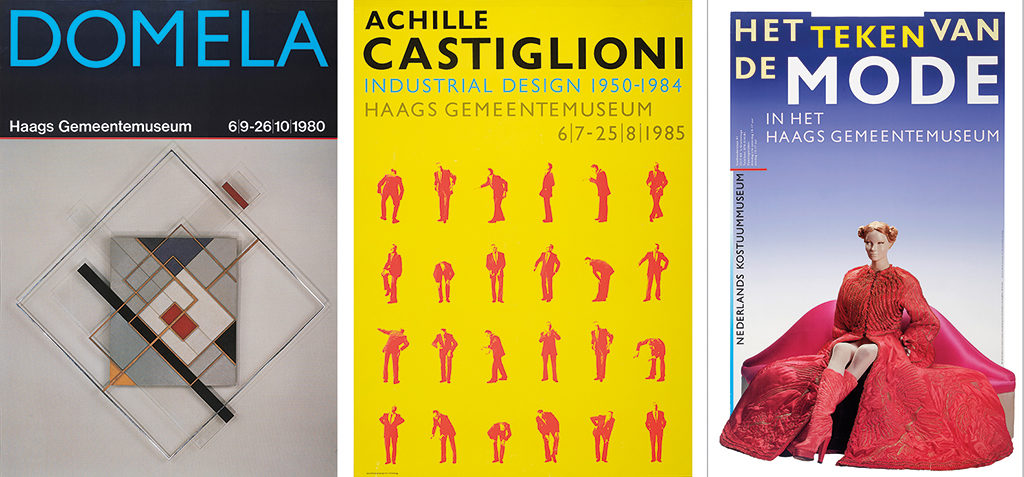

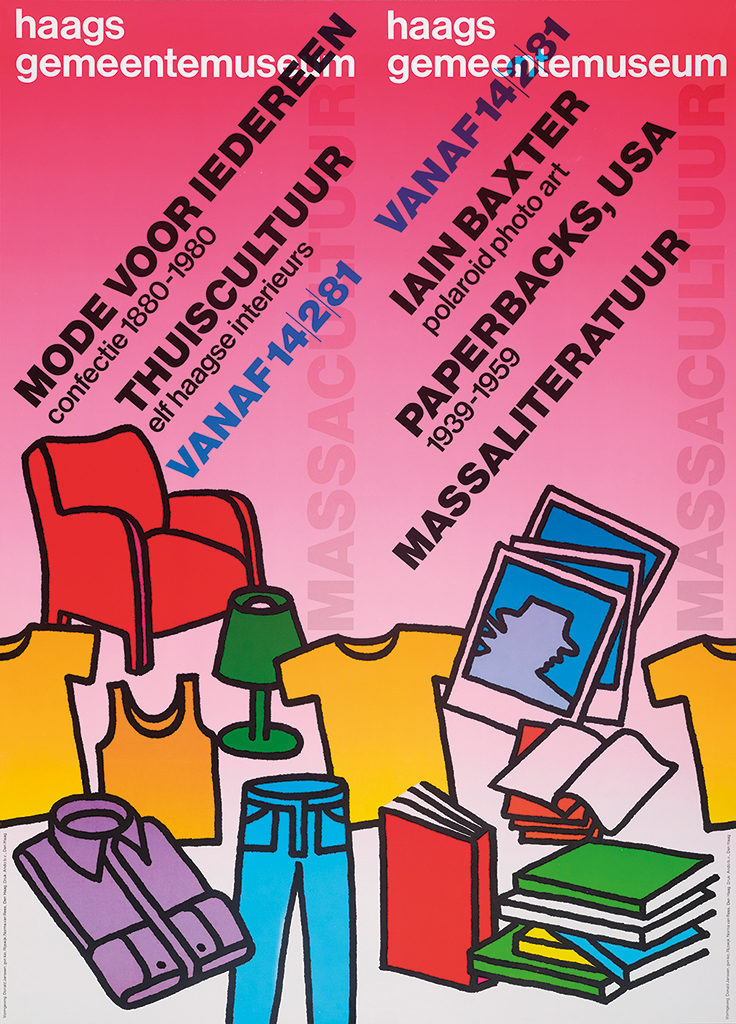

Arja and I got to know Kees Broos and his wife Liesbeth Brandt Corstius after they’d bought some of Arja’s work from Fenna de Vries Gallery in Rotterdam. Kees was a curator at Haags Gemeentemuseum; he often visited our studio apartment, sometimes in the company of author Maarten Biesheuvel. Kees invited Arja to have a solo show in the museum (in 1971), on the occasion of which TV journalist Ageeth Scherphuis interviewed Arja. In 1977, the year Theo van Velzen became the museum’s director, Kees Broos and Flip Bool invited me to participate in the exhibition Zes Haagse Ontwerpers (Six The Hague Designers). The other five designers were Paul Driessen, Gert Dumbar, Heinz Edelmann, Ootje Oxenaar and Jaap Vegter. I first met Van Velzen while preparing for the exhibition. In the commemorative volume Theo van Velzen, Directeur Dienst voor Schone Kunsten 1977-1986published in 1986, Henk Overduin wrote: “Just before Van Velzen arrived, Janssen had already designed his first poster and catalog, for the exhibition The Norwich School (curator: John Sillevis).It had to be: Janssen and Van Velzen and his staff would develop a strong, long-lasting and friendly collaboration.”

During all of Van Velzen’s regime in The Hague I managed to remain Van Velzen’s favorite freelance designer. He gave me a free rein, only demanded a strict separation of text and images and the explicit positioning of the name Haags Gemeentemuseum. Henk Overduin: “Donald Janssen’s approach to his job fits seamlessly with the museum’s structure. The complexity of the collection demands flexibility; so does the multidisciplinary staff, and the designer not only has to have a strict sense of style but also to be a capable communicator.” In the ten years I worked for the museum I designed an identity program and scores of exhibitions, catalogs and posters. I learned much about museum design during these years: Haags Gemeentemuseum was my laboratory and testing ground.

Early in those years Harry Verburg, the director of the Arnhem art academy, asked me if I would be willing to succeed Gijs Bakker, who was leaving the industrial design department then called ‘Design in metal and plastics’. How could I say no, this leading teaching position was just made for me. The teaching staff included Frank Ligtelijn, Joep Sterman and Onno van Dokkum; together we trained many a new design talent who since then made a name of their own.

Arja and I moved from Rijswijk to the chic Statenkwartier in The Hague. It was the time of the architects group Van Mourik Vermeulen’s involvement with the renovation and extension of PTT’s Post Museum. Their experience with museum design was rather limited, which was why Dick van Mourik asked me if I was willing to advise and contribute to the project. I joined the team and, still a freelance designer without any assistants, I developed lightweight aluminum displays, magnetic linkable information panels, exhibition islands, color schemes, a signage system, and an identity program. It was a huge job. In 1986, Prince Bernhard was invited to officially open the museum.

The growing number of design projects created a situation in which I could no longer function without assistance. Soon there was Ontwerpbureau Donald Janssen and its team kept growing. Had I in the past for large projects teamed up with other freelancers, like Ton Martens, Adelbert Foppe and Françoise Berserik, now I needed stability and continuity also of design vision and approach. Norma van Rees became my first staff member (she had graduated from the academy in The Hague in 1980). Five years later, Victor de Leeuw took over. He was joined by Jan Hubert, Jeanne Smits and later also by Jeroen van Lente, all of whom came from St. Joost art academy in Breda where they’d been students of Jan van Toorn. The design team was completed in 1987 when Hans Frings joined, who had studied in Arnhem. We designed more than museum interiors and exhibitions.

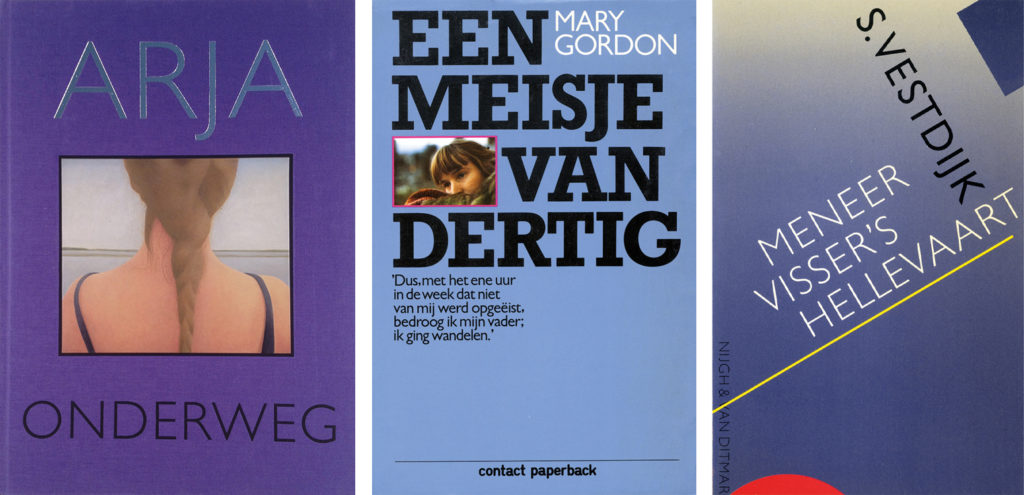

Print design always had our attention and we worked for publishers such as Nijgh & Van Ditmar, Bert Bakker, Waanders and Van Spijk on book covers, book typography, catalogs etc.

While I was deeply involved in museum projects my young team worked also on the reconstruction of the old town wall at Rotterdam’s railway station Blaak; on the corporate identity program of the business bank Theodoor Gilissen Bankiers; and on furniture for NSM Spaarbank, like Gilissen also in Amsterdam. We became more experienced at museum interior and exhibition design by redoing the theme halls Endogenic archeology and Exogenic archeology for Museon in The Hague, the exhibition design of The Hague’s new history museum, and the rather unusual exhibition Hollandse Waterlinie (Dutch defense against the sea) in Fort Asperen, together with Marijke van der Wijst. Museums kept knocking on our door. Less graphic design, more industrial and 3D design came to our design tables. We became experts at the design of temporary and semi-temporary, interactive, evocative and educational exhibitions for museums and government departments. We were becoming a multidisciplinary design agency.

In 1986, the Noordbrabants Museum moved from the St. Jacobs Church to the under supervision of architect Wim Quist magnificently restored and much larger Governors’ Palace in Den Bosch. Museum director Margriet van Boven asked me if I wanted to design the identity program and the exhibition spaces. Two years of intensive discussions with her curators Charles de Mooij (now the museum’s director) and Maureen Trappeniers followed, under the never relenting critical eye of the museum director. It was all worth the trouble. One year after the new museum opened, in 1989, it was rewarded by the first ever Prince Bernhard Foundation’s museum prize, “… for the exemplary way it transformed a monument, in which its collection is sublimely conserved and displayed.” We continued to be involved with the museum’s exhibitions for another ten years.

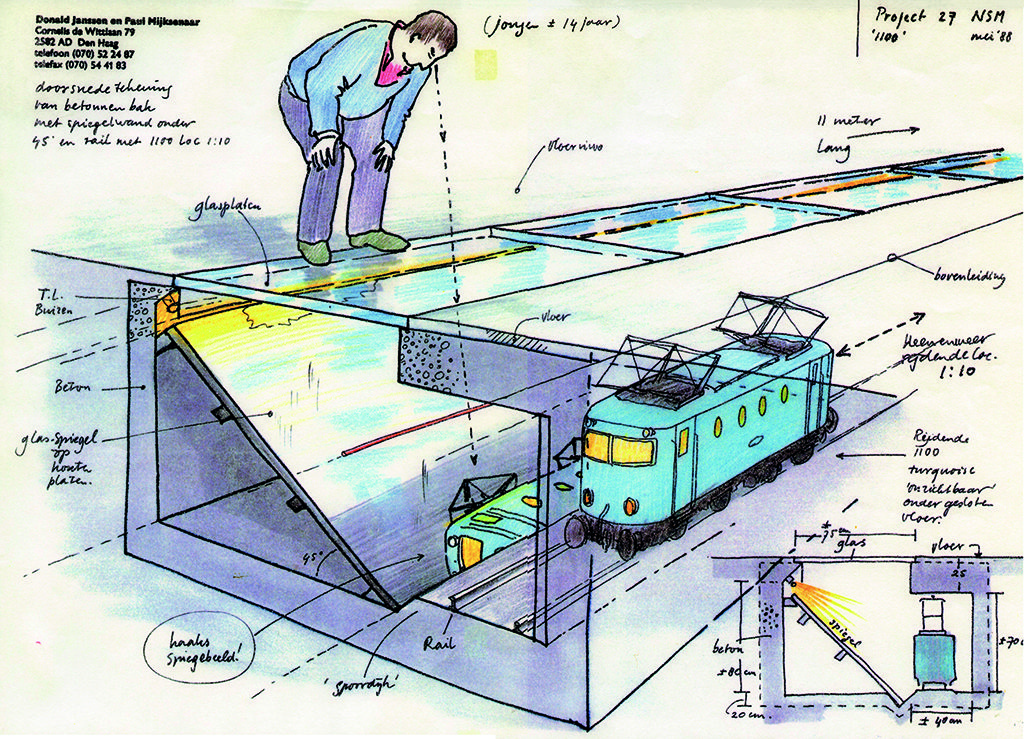

A new phase: Paul Mijksenaar and I were invited to collaborate on a proposal for the design of the exhibition spaces in the Nederland Spoorwegmuseum (railway museum) NSM at Utrecht’s Maliebaan station. For the classical symmetrical building dating back to 1874, with its high central hall and two wings, we designed “a surprising, clear, obstinate, and as timeless as possible” solution, which was accepted without much need of changes even if the budget almost quadrupled. To facilitate the collaboration, Janssen & Mijksenaar established an LLC, which after starting in 1987 survived until 2006. First things we bought in 1987 were three fax machines for the communication between the two participating studios and the museum.

NSM curator Lex van Marion and we teamed up well; we found the right design style fitting the robust solidity of the railways by using lots of well-defined, choice steel and glass applications. Ton Fichtinger (for the Dutch railways NS) was the museum restoration’s architect. Steam and loud noises accompanied the official opening in 1989. The museum received the ICOM Reward, Dutch PTT had three special postage stamps designed by Gert Dumbar, Paul Mijksenaar, and I – and I am happy to recall that, in 1989, my design was selected as being “the most beautiful” by the general public.

Later in the same year, Andrew Scott, the director of the London Transport Museum, and other ICOM delegates came to visit the museum in Utrecht. I happened to be around, and curator Lex van Marion introduced met to the group. Scott took me aside; he was looking for a design team for his own museum. Sometime later I was invited to do a studio presentation in London, where I met members of the museum staff as well as the proposed architect, George Butlin. Before the end of the day I received a phone call from Andrew Scott: they had chosen us for the exhibition design. The decision left us as speechless as it did London design circles…

LTM, the London Transport Museum, can be found in Covent Garden, in an old Victorian flower market from 1880. We proposed to tell the complicated social and technical history of two-hundred years of public transport in London on fourteen themed “islands” placed on a route of different levels.

For the sixteen meter high building with its large glass roof we designed a steel plateau that was to carry two locomotives and two wagons (weighing a total of 200 metric tons). The plateaus were to be reached on two stairways and a curved pedestrian bridge, passing two climate-controlled UV-free glass galleries where photophobic images and posters would be presented. Our proposal enlarged the exhibition space by some 30 percent, from 1750 m2 to 2500 m2. Close to one-hundred interactive information units were included, also touch screens with film, audiovisual presentations, 3D tableaus, aromatic machines, and simulators of locomotive, metro and bus movement and control. In newly designed free-standing displays (of steel and glass) magnificent scale models and other objects were presented. A new approach to lighting did very well to show each detail of the exhibited objects. We worked so well with the museum’s young curators, Belinda Betts and Mark Dennison… All exhibition furniture was made in Holland by Glascom and Bruns. The project timeline covered three years, during which the museum had to be closed for only nine months. The budget? Over four million pound Sterling. Eleven of my staff designers and four of my interns worked on the project. We must have been the first Dutch design group ever to be involved in such an enormous design project in the United Kingdom.

The project demanded a lot of space to create models and objects. Therefore, we moved to a more spacious 19th-century building in Duinoord, in The Hague. We could grow again. The team was extended by designer Vic Sol and the architect Jack Huyskens; sometime later Pieter Aartsen and Jeroen Franken joined. Ontwerpbureau Donald Janssen became Donald Janssen Ontwerpers bv, DJO.

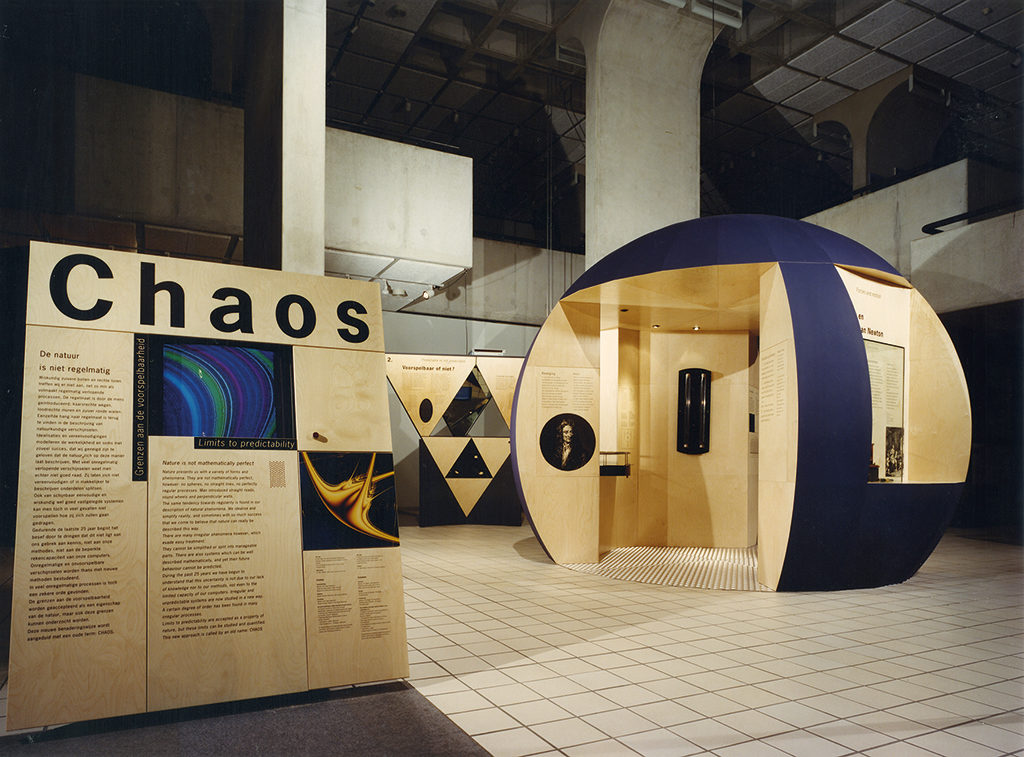

The 1990s were exciting, not in the least because the digital era also invaded our studio. Apple computers, still highly expensive, appeared on to our desks. And apart from our work for LTM we had other big projects to pay attention to: the traveling exhibition 100 years ESSO for ESSO Nederland; the 1992 Floriade; the exhibition Chaos!; and the exhibition halls Electronica and Waterland for the Museon in The Hague. Then there was the design of the Amsterdam headquarters of the Postbank; the interior design of the visitor center Nieuwland Poldermuseum in Lelystad; the TEFAF exhibition Treasures from the Hermitage; the Space Expo in Noordwijk; Drents Museum in Assen – all time consuming, complicated projects. We didn’t have to wait long for follow-up projects from the U.K.: furniture for Peoples Palace in Glasgow; a pre-feasibility study for a new transport museum in Edinburgh. Also, from (former East-) Germany: the new exhibition design of the Städtische Kunstsammlungen Chemnitz.

The exciting aspect of exhibition design is the storytelling by means of space, objects, interactive tools, sound, color, smells; the mixture of these elements create long-lasting memories.

For Frits Duparc, the director of the Mauritshuis museum, over a period of nine years we realized twenty exhibitions including the successful blockbusters Johannes Vermeer and Rembrandt zelf (R. himself). We also designed catalogs, posters and furniture. At our studio, Victor de Leeuw was our “Mauritshuis Man”. In 1998, after thirteen years at our studio, he left us to become a freelance designer. The Mauritshuis happily decided to continue their collaboration with Victor.

Until the 1990s, the Nationaal Natuurhistorisch Museum’s several science departments were dispersed over different Leiden locations. In 1998, they were brought together in a new building designed by architect Fons Verheijen: Naturalis. The museum’s collection is enormous: more than 10,000,000 objects are conserved in the building, the largest and, at a cost of 137 million guilders, the most expensive museum to be built since the end of WO II. The museum’s director, Wim van der Weiden, and his staff selected six studios to help them with the interior and exhibition design including one from London and one from New York. In 1996, DJO was commissioned to install two huge collections on two of the building’s levels: on roughly 2500 m2 of the total space of 5000 m2. The top floor was to show “the immense wealth and astonishing diversity of nature” in a Nature Theater. On the level below the top floor we had to present “the origins of life on Earth” in an Ur Parade. The central theme was, of course, the Earth as one huge, dynamic system. After the sub-themes had been defined, long months began during which we submitted proposals, and presented sketches and drawings as well as mock-ups and models. For the large collection of animals and plants we designed animal “plateaus” and for minerals and rocks, “cabinets”, and we proposed a hanging oval glass display for five-thousand plants, butterflies, toadstools, fish and more. This display became 16 m long, 9 m wide and 3 m high. The construction came with a high cost and no Dutch builder came forward to accept the challenge. At last, Glaverbel from Belgium (now AGC Glass Europe) came to save the day and agreed to help us with “the experiment”, as they called it. The display has been up for eighteen years already and never caused any problem. The Ur Parade on the lower floor had a spiral pattern. From the trunk of “the family tree of Life” spread out 47 display islands that appear to be excavations; these take up the whole floor.

Naturalis was officially opened by Queen Beatrix on April 7, 1998. Since then, millions of visitors have explored the museum. Nine DJO designers worked on the project: Victor de Leeuw, Jan Hubert, Jeroen van Lente, Bart Bekooy, Michael van der Zee, Pieter Aartsen (now head of exhibition design at Naturalis), Philip Verschueren, Dennis Wienand, Brigitte Gootink, as well as three interns.

We entered the 21stcentury by moving to a new studio space in a restored monumental building designed by the architect Jan Duiker. The office building, in Scheveningen, was to be the home to photographers, architects and landscape designers, industrial designers and graphic designers, consulting engineers etc. Of course we actively exchanged ideas and experiences, and we collaborated on several projects. Peter van der Toorn Vrijthoff (HTV Architects) advised me when I was designing the Limburg pavilion of Floriade 2002, for which giant event we (participating in a consortium) also had to deliver the pavilion presenting the national government’s department of agriculture, nature and food quality.

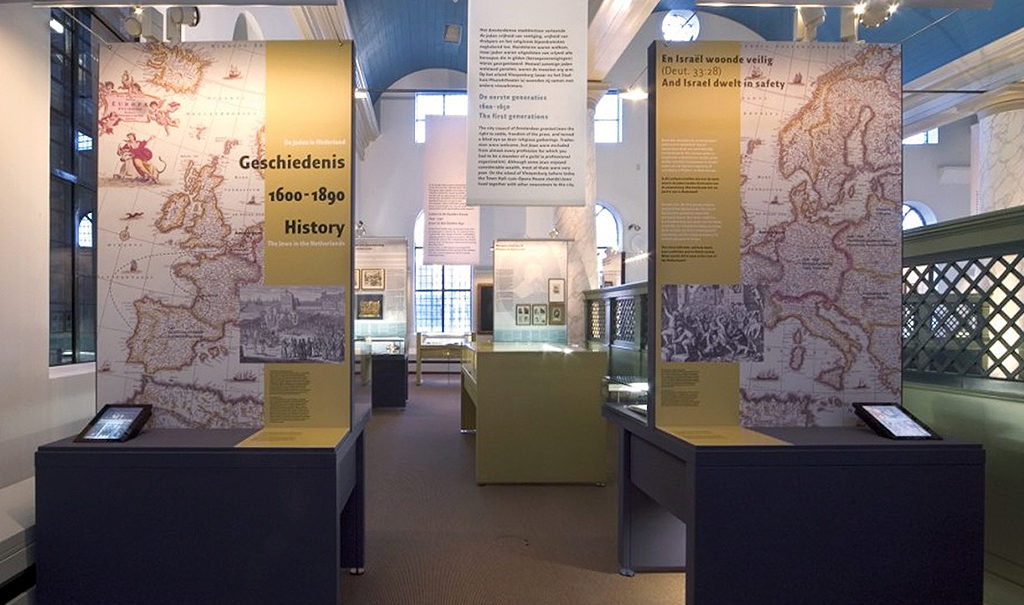

Another client we worked for in the same period (2002-2004) was the Jewish History Museum in Amsterdam. One of the most impressive and interesting museums we ever helped design, the building originally was home to four synagogues. Three other studios were involved in the renovation and exhibition design; each of us had a section of the museum to concentrate on. Rabbi Edward van Voolen introduced us to the Jewish religion and heritage. Our job was the design the permanent presentation of the Grote Synagogue; the theme of the big hall was Religion, and in the Women’s gallerywe had to show “the Jewish history of the Netherlands from 1600 to 1890”. My Dutch Reformed background and engaged social consciousness were faced by the Rabbi’s vision of the Jewish history, the diaspora and the holocaust, as well as the Palestine status quo. An interesting confrontation.

The Jewish museum tells the story of the Sephardic Jews who came mostly from Portugal to Amsterdam. Their history differs from that of the Ashkenazy Jews, who came predominantly from eastern European countries. We enjoyed working with the magnificent museum collection, all sorts of interactive tools, and their unique and costly furniture; there was a generous budget and perfect lighting could be installed. Michel Krielaars wrote in NRC Handelsblad of January 8, 2005: “Everything of this new, permanent exhibition (called ‘Religion’) about Jewish traditions and customs is presented in a perfect way as we know only from the great American museums such as the Smithsonian in Washington.” The paper gave the presentation *****.

In 2005 (after celebrating my 62ndbirthday) I decided to slow down from the energy-consuming management of the busy design studio and its crew of enthusiast young professionals. Arja and I came to the decision to cut back slowly, then continue as I had started in the profession, as an independent designer without permanent assistance. After we had informed our staff, it took us two years to get there. We had to say farewell to colleagues who had become friends: Jan Hubert, Michael van der Zee, Bart Bekooij, Pauline Koopmans, Karel Buijn, Nienke Houwen. Jan Hubert had been a team leader for eighteen years and had been the much appreciated teacher of young designers and interns; he started his own studio.

But, shortly after taking up as a freelance designer, I understood I needed the assistance of someone who really knew about digital presentations. Industrial designer Karel Buijn, who had done computer animations while DJO worked for the Jewish History Museum, now worked freelance and I asked him to digitalize my proposals and sketches. Together we worked for Stadhuismuseum Zierikzee (curators: Peter Priester and Minke van Meerten); Terra Maris in Oostkapelle (curator: Carolien Schaap); a series of exhibitions for Museum Huis Doorn (curator: Cornelis van der Bas); and the floating information center for Overhoeks, a housing project in North-Amsterdam (with Sanna Helmer).

I kept busy also as a visiting professor at the Reinwardt Academy in Amsterdam, where I taught exhibition design.

From Elburg, in the Dutch “Bible Belt”, came a follow-up of the Jewish History Museum project. A group of very devoted townspeople founded Museum Sjoel Elburg and their project manager Frederieke Jeletich asked me to handle the interior redesign of the old synagogue building. The museum had only a small collection but was a real treasure chest full of interesting stories and memories. In the end, we had created a very intimate, tranquil, almost cosy place where fascinating tales are told about the Jewish community in Elburg and about WW II. Tom Bergstra is the museum’s dedicated director; he is assisted by a large group of volunteers. In 2010, Sjoel Elburg’s uniqueness was recognized. This “most beautiful of the small museums in the Netherlands” received the Montblanc Museum Award.

Sometime later, in 2015, Jelle van der Toorn Vrijthoff asked me if I would be interested in doing the redesign of the Freemasonry Museum in The Hague. Jelle, an important Freemason, overwhelmed me with philosophies and information about Masonic history and rituals, and he introduced me to some of their most interesting members. The museum had to be not just an esthetic experience with the collection catching all the attention, but rather a storybook. It was wonderful to work with Jelle, who has a background quite similar to mine. We finished this task in 2017 and worked not just for the museum part of the building, but also for their offices and the Masonic Temple.

Over the years, my interest and fascination for art history and cultural history and the collections that were assembled in their specialized museums had only grown. Each new project started with the curators taking me deep into their depots to make me familiar with the atmosphere and uniqueness of their objects and treasures. All museum curators told me the most fascinating stories, and it was my job to listen closely, interpret these stories, and as best as possible translate them into strong presentations.

Donald Janssen

born on 7 June 1943, Den Haag

Author of the original text: Donald Janssen, oktober 2019

English translation and editing: Ton Haak

Final editing: Sybrand Zijlstra

Portrait photo: Aatjan Renders