“Growing up in a progressive family with four brothers stimulated independence, initiative, and visions of our own future and our own place on earth. Taking the easiest way out was not an option, we needed challenges. Mine was to find something that would allow me to combine a career with raising kids. At the time, this was unthinkable: a woman who started a family had to stop working. Also, I wanted to be able to pay for my own house before I was thirty.” Anneke Huig tells her story in her own words.

Anneke Huig at her desk, being interviewed by Wessel Franken and Lieneke van Schaardenburg about women in a men’s world (1966). Photo: Bob Westdorp

I was born in the summer of 1940 during a thunderstorm and a bomber alert. My father was a construction engineer from the Zaanstreek (north of Amsterdam). As from the early 1950s, he was attached to an architecture and city planning studio, he taught civil engineering at a real estate course program and he was a licensed real estate agent himself. My mother came from the famous ‘art colony’ in Laren and was a fashion designer. Before WW II she wrote a column for Algemeen Handelsblad (daily newspaper). The smell of print entered my nostrils at an early stage in my life. Huig Printers in Zaandam, who printed reproductions for the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, was owned by two of my father’s cousins. Neither of them had children and fully expected my oldest brother to succeed them, because he studied at the graphic school. My brother said thanks but no thanks and tried his luck in America.

Education

I attended the Geert Groote Vrije School (free school) in Amsterdam. They granted their teachers the freedom to adjust their programs at their own discretion. If classes were too demanding for a pupil, a classmate was expected to jump in and help. I was about twelve when I discovered that in a German grammar book the case forms were rather disorderly presented. I made some neatly arranged lists for a dyslectic classmate, which served her well. In a way this presaged my future occupation: presenting information clearly, creating order in chaos.

Workweek with IvKNO students at Terschelling island (1959).

The school gave ample room for all the arts, but I was interested most in the science classes. Still, I decided to continue my education at IvKNO in Amsterdam, the predecessor of the current Gerrit Rietveld Academy, which in those days was located next to the Stedelijk Museum. I chose illustration, typography and advertising design. My teacher Wim Brusse predicted I had a shiny future in graphic design. I graduated in 1960.

Knoll International had a showroom of their American design furniture in Amsterdam and was the first company to commission me as a designer. I produced sample books with furnishing fabrics, photos and text in calligraphy. Knoll director Wim Janssen’s secretary left because she was getting married (!) and he offered me her job, unless I wanted to continue in design. In that case he would be willing to recommend me to some of his business acquaintances. Of course I chose for the latter. Among those to whom he wrote were Proost & Brandt (paper wholesalers), Willem Sandberg, Wim Crouwel, Otto Treumann, Gerard Wernars, Toussie Salomonson-Keezer and Benno Premsela. Wim Crouwel, already of international fame at age 32, was the first one who reacted. On May 15, 1961, I became his first assistant. His studio was at Reguliersgracht, in the attic of photoype printer P. Rijnja. The terms of employment were from 1919, but it was the start of the best five years of my life – very exciting, enervating and instructive years. I discovered all the ins and outs of graphic design.

Total Design

Some eighteen months later, Wim Crouwel told me about the plans for Total Design. He and Benno Wissing and Friso Kramer had decided to form a partnership and had found two business partners in Paul and Dick Schwartz. Ben Bos was to be their chief of studio and they wanted to start with a staff of five assistants. Wim raved about the unlimited possibilities of this new – unique and pioneering – agency, which was going to have Keizersgracht 567 as its home base. I wasn’t much attracted to work under a studio chief instead of Wim Crouwel personally, but Wim convinced me and I signed up for three years. Jack Jacobs, who had also worked for Wim previously, joined the team too. It soon became clear that the arrangement with Ben Bos as ‘middle man’ between the designers and their assistants did not work; there were irritations and after a few months, the direct lines between designers and assistants were reinstated. Ben got his own team.

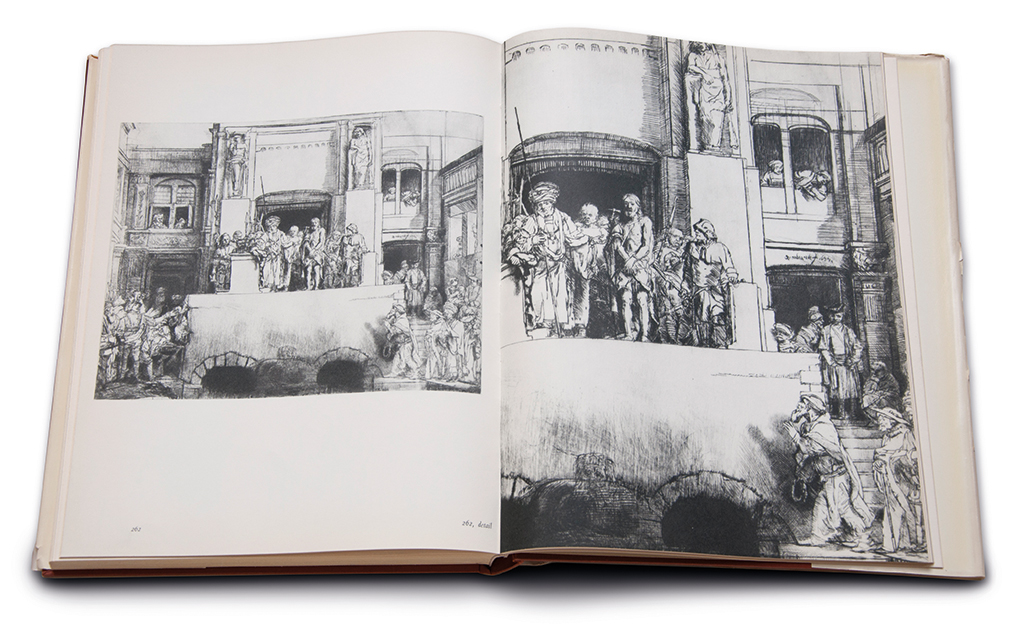

Gradually, the assistant-designers were allowed more freedom, sharing more responsibilities. The first big project I handled almost all by myself was the monumental book Rembrandt: The Complete Etchings, three-hundred pages with hundreds of etchings that had to be reproduced 1:1. At this time the building was being refurbished so I spent many an evening (and night) in the deserted studio, finally able to concentrate without disturbance. The Dutch edition was published by Becht, the English-language edition by Harry N. Abrams, New York. It was selected as one of the 50 Best Designed Books in the Netherlands, but unfortunately my name wasn’t mentioned in the colophon.

Book ‘Rembrandt’ with all his etchings size 1:1. With Wim Crouwel, Total Design (1963).

In 1963, director Edy de Wilde left Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven for the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. A long-time friend of Wim Crouwel, he commissioned TD to design what became an extensive series of catalogs and accompanying posters. I think I designed at least forty catalogs and a good number of posters and again I spent many an evening hour in the studio and at the printing press. It wasn’t before late 1965 that TD finally started adding the names of assistants to the colophons. That decision came too late for me.

A dinner party during the 1964 Icograda Congress in Zürich. From left: Annie Crouwel, Emy Wijt, Wim Crouwel, Anneke Huig, Friso Kramer, Haruko Koguchi, Nina Gerisma and Dick Schwarz. Photo: Comet Photo AG, Zürich

In the weekend of October 30 and 31, 1965, a convoy of huge tanker trucks would receive the new logo of oil company PAM as part of the large-scale introduction of their new corporate identity. I represented Benno Wissing, the designer of the corporate identity, at the location in Kampen where the operation took place. The transformation of the other vehicles of the PAM fleet in Rotterdam was being supervised by Benno himself. Every ten minutes, a truck drove up. It was my job to point out the exact placing for the logo and the lettering, assisted by André (That Hwie) Kwee from Omniscreen and his small army of helpers who attached the stickers. The next day, the later famous restyling could be seen all around the country.

A new phase

The end of my three-year contract with Total Design was approaching. It had been a wonderful time but I had decided I was going to leave. While discussing my departure and my rough plans for the future, Wim said something remarkable. He said he could understand I wanted to leave, because at TD there was no way to the top for me as a woman, in spite of my professionalism and dedication. Even though I had no ambition whatsoever to become a director, I found the mere fact shocking.

All I really wanted was to move out of his shadow and make good work under my own responsibility. I did not want to be somebody’s assistant forever. Plans for an equal partnership with my dear colleague Will van Sambeek did not materialize. I have fond memories of the evenings of heated discussions in his attic room in Breda about the use of small caps and other typographic preferences. Another option was to go to the US for a year. I had worked so much overtime – which TD could not pay out – that they gave me three weeks of extra vacation to visit George Koizumi in New York. George had been Benno Wissing’s assistant in the first TD year and in exchange there was a job for me in New York. The American conformist mentality was too oppressive for me, so I decided not to take this opportunity.

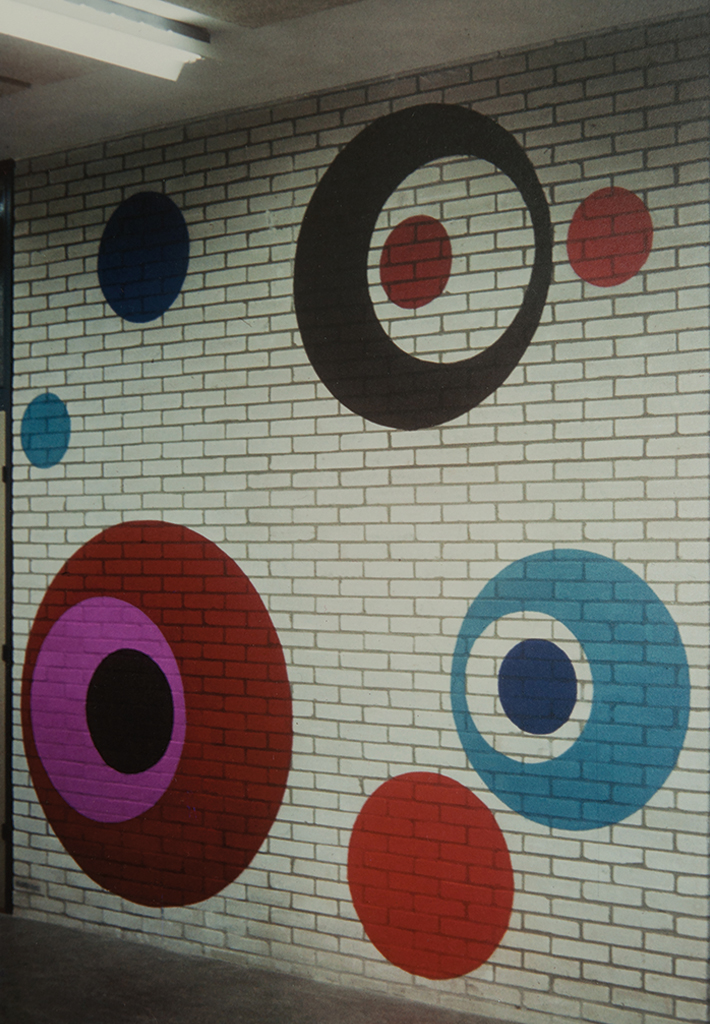

Anneke Huig installing a wall design in Winschoten (1967). Photo: Greet Smit

Parts of a wall design for Philips tech services, Alkmaar (1966).

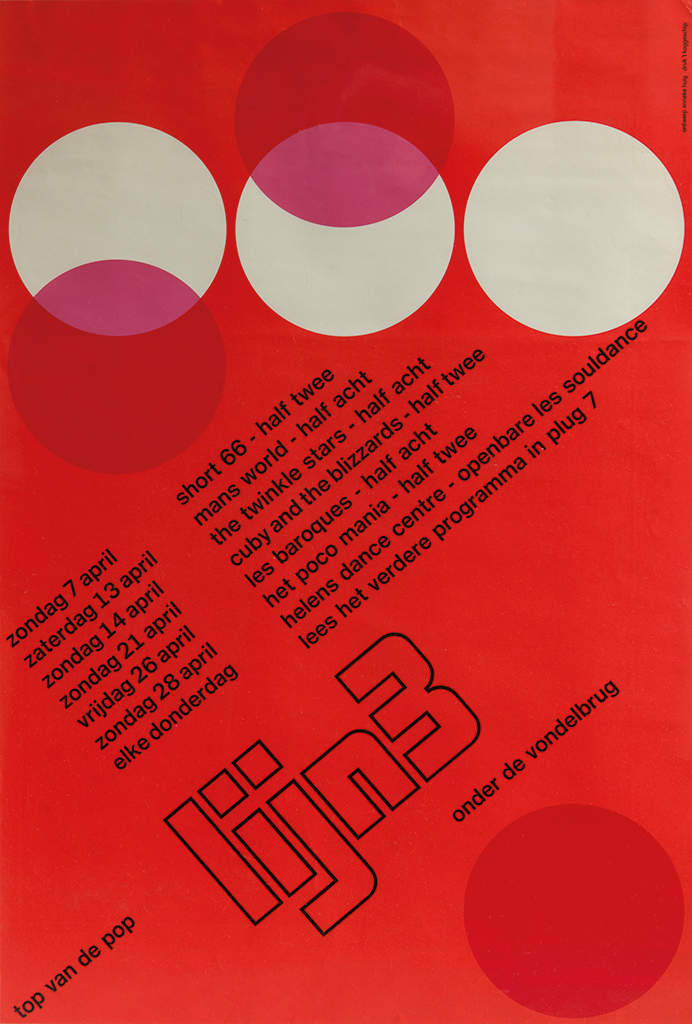

May 15, 1966. Exactly five years after I had first joined Wim Crouwel, I had my own studio, curious to find out what I could produce. Apart from the work Wim had given me and the wall paintings I had already been making on a regular basis for several architects and municipalities, new clients soon appeared: the Netherlands Institute of Physical Planning and Housing, the Haarlem cultural council, Senefelder printers, the ‘beat cellar’ in Vondelpark, and others. I was busy. Wim Berkhout, with whom I had studied at IvKNO, brought up the possibility of a joint studio. Dick Dooijes wrote about my designs in Drukkersweekblad, the graphic industry’s weekly.

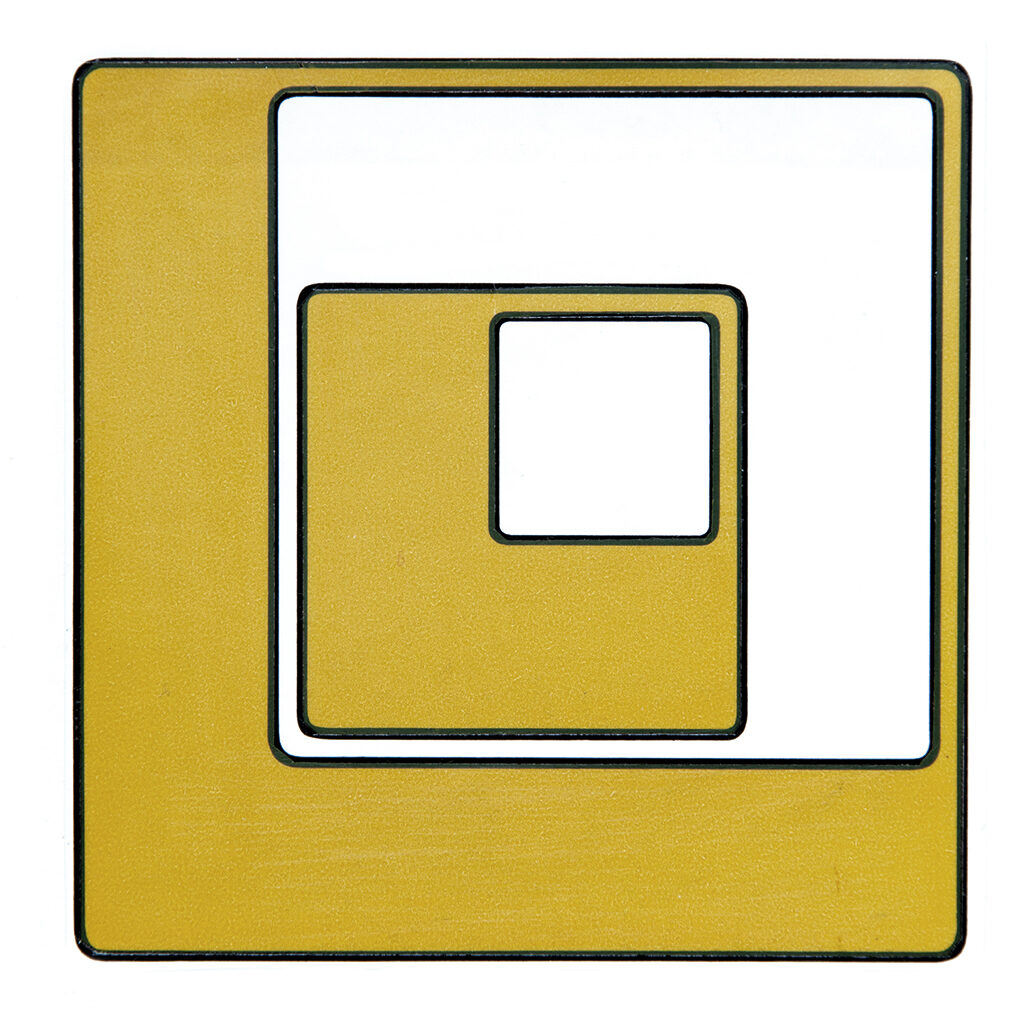

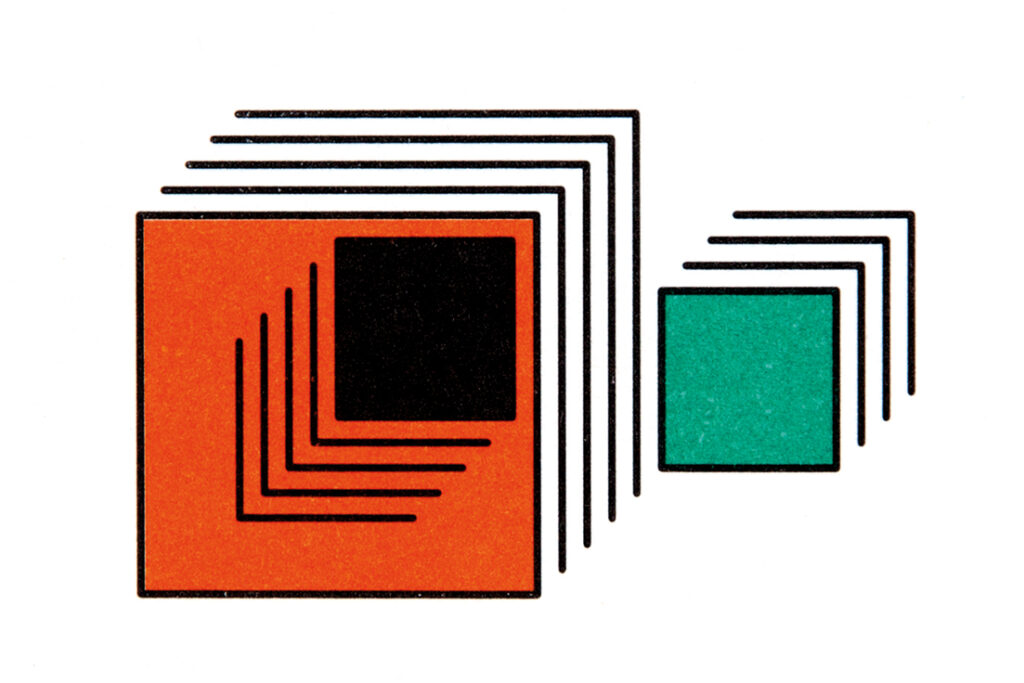

Logo for the Dutch institute of environmental planning, The Hague (1968).

Calendar for Senefelder printers with images by Albert Lauw, Amsterdam (1969

Poster for ‘Popkelder Lijn 3’, Amsterdam (1968).

The only problem that bothered me in that period was the housing shortage. In my small rental room, located in a house on the Amstel river, I could not receive clients. Eventually, I bought a small property on a canal, with a separate work space. Since my teenage years I had put aside a percentage of my earnings, as my father had advised my brothers and me, which I could now benefit from. Because I could not move into the work space right away, Jurriaan Schrofer offered me a part of his studio, where I could also invite clients for meetings. Jurriaan also pushed me to send my work to GKf, the association of leading Dutch designers, and they accepted me as a member.

Brochure for “green” action ‘Schone Randstad Zuid’ with photo by Dolf Kruger (1970).

Meanwhile, the graphic world was in turmoil. Offset printing pushed out letterpress, threatening tons of lead type, typesetting machines and hand and platen presses to be sold for scrap. Some of the rejected type and presses were saved by enthusiasts. Pieter Brattinga was one of the initiators of ‘Typotent’, a foundation that tried to save print workshops in Amsterdam, where amateur typographers and printers could experiment with graphic techniques. Van Steijn printers at Warmoesstraat offered a space in their attic, where real typographic gems were created. Brattinga was joined on the ‘Typotent’ board by Jaap Kaal, Dick Dooijes, F.G. Meijer, Th.H. Oltheten, Emile de Vries and the lady Anneke Huig. I could make full use of my organizing talent when the attic had to be prepared to become a print workshop.

Otto Treumann and Gasunie

When Otto Treumann traveled to Switzerland or Israel for several weeks, he would give me the keys to his home and studio so I could take care of his projects during his absence. When I could spare the time, I also assisted Otto in the design of three of his big projects: a calendar for the City of Amsterdam about the city’s market places and two voluminous books. In gratitude Otto added my name to the colophons. I almost wished he hadn’t. All three projects were awarded and now my name was connected to his. I had crawled out from under Wim Crouwel’s shadow, only to feel Otto’s shadow descend on me. We laughed about it; he fully understood my dilemma.

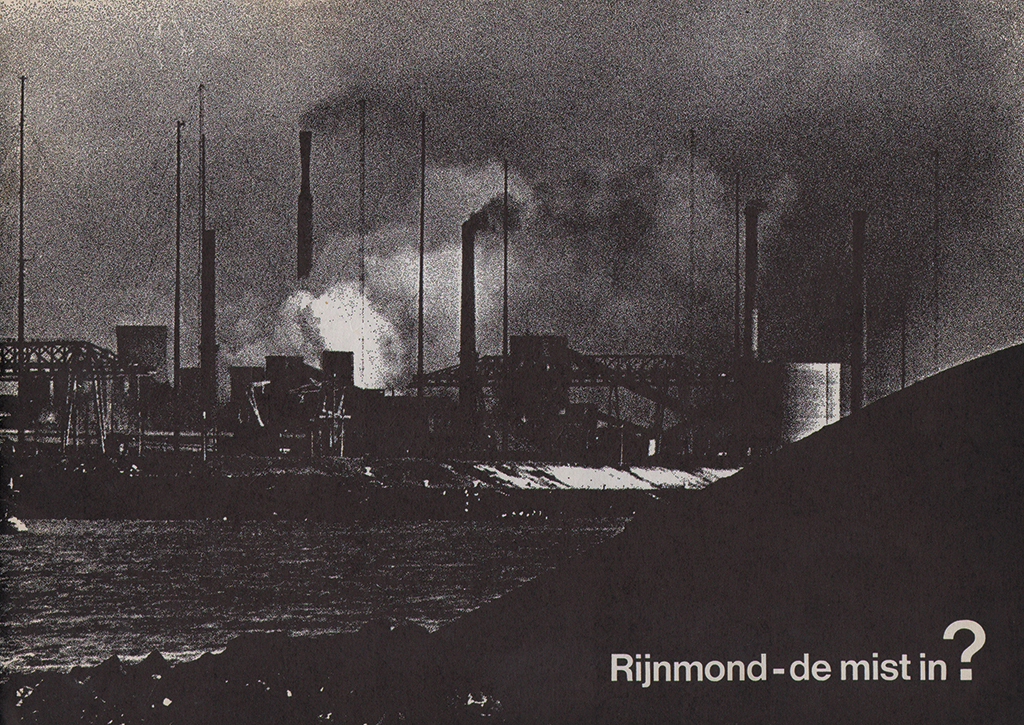

Introduction and instructions, at the start of the new corporate identity program, Gasunie (1971).

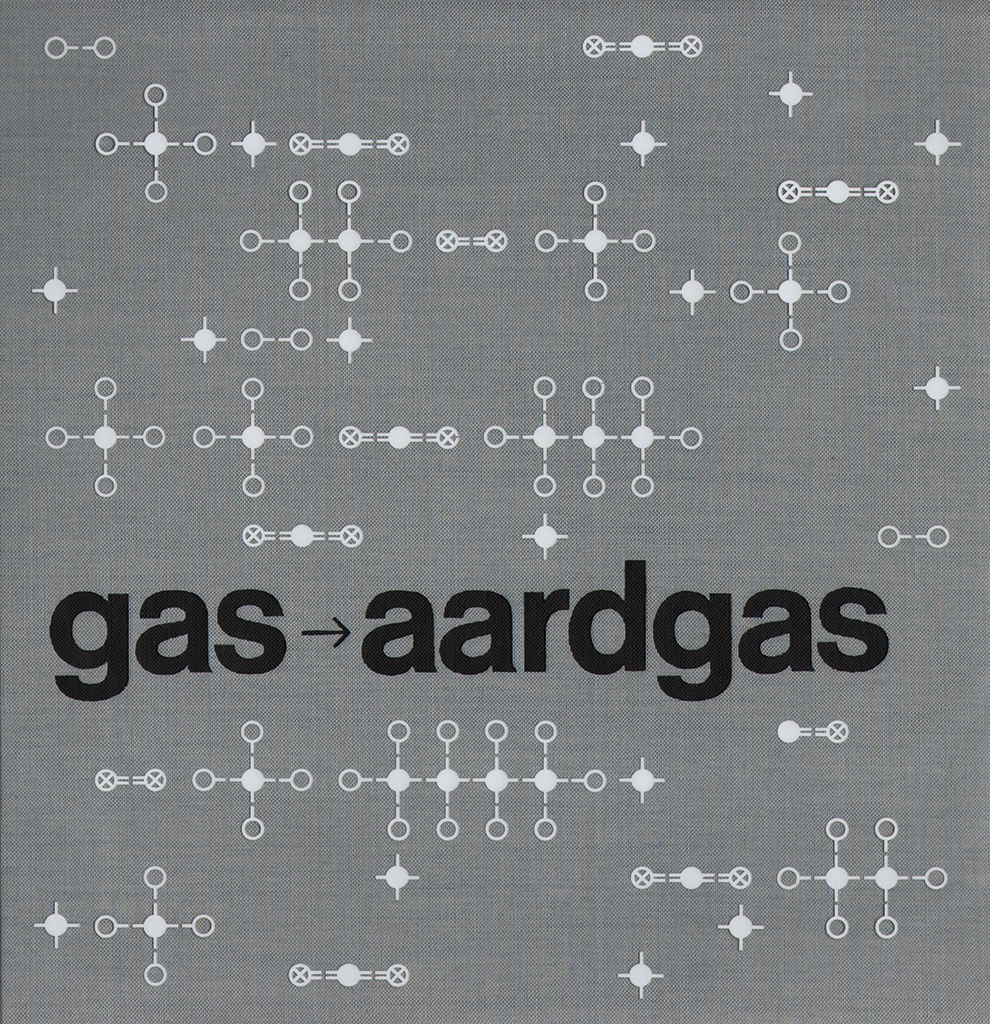

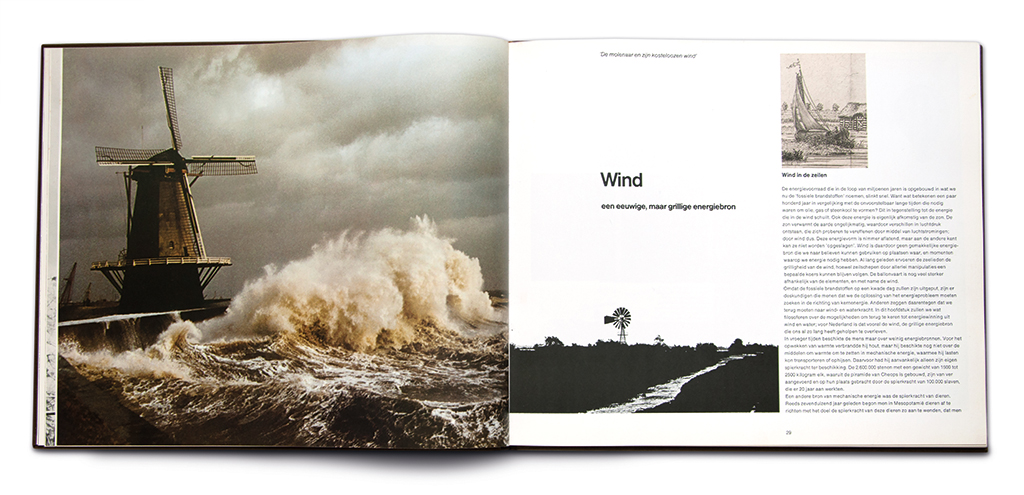

Book ‘Gas > Aardgas’ (gas > natural gas) for Gasunie (1972).

In the early 1960s, Otto Treumann had designed the new natural gas company Gasunie’s logo. In 1968, their company headquarters in Groningen was approaching its completion. As soon as it was ready to receive the staff, hundreds of employees from all over the Netherlands would move to Groningen. Otto was asked (posthaste) to add the new logo to a series of business forms. Forms were not exactly Otto’s greatest passion, so he asked me if I was interested. We drove to meet the Gasunie management and I was introduced as someone with experience who used to work at Total Design. I got the commission and Otto withdrew.

Initially, the gentlemen of the board were rather skeptic about me. There where no women in the world of pipefitters and pump jacks, except behind a typewriter. They changed their minds after the first forms came from the printing press: on time, printed well, perfect of color and with a design that was fine-looking and professional. A victory for substance over superficiality. I responded rather matter-of-factly to their amazement: “But of course – it’s my job.” Soon more commissions followed, for brochures, leaflets and also a calendar.

Calendar with cut-outs by Frouke Goudman-Cupido for Gasunie (1974).

Brochure, theme ‘Energy-conscious construction in Sweden’, for Gasunie (1980).

Helicopter with Gasunie lettering (1986).

Jan Visser became my contact at Gasunie. He originally came from NAM (a Dutch oil company) and was a member of Gasunie’s communication team with responsibility for Gasunie’s staff magazine Gasuniek. We hit it off and complemented each other: he knew how to explain my creative ideas and push them through the organization. We turned out to be an excellent team.

Commemorative publication, theme ‘Mankind and energy’, 15 years of Gasunie (1978).

Jan was a widower with a son and a daughter (then 10 and 14 years old respectively). I became one of the family and eventually Jan and I got married. We moved to the countryside in Groningen province. I gained parental power over two stepchildren, which I gladly took upon me, but I also lost some of my independence. I partly lost my legal competence as well, which would later bring me in a lot of trouble financially. Together, we added two children, a daughter in 1969 and a son in 1975.

I realized that our professional collaboration might become the subject of scrutiny now that we were married, because it could be seen as a conflict of interest. After discussing this with the head of the communication department I got permission to continue my work for Gasunie, on the condition we kept it quiet. I had to send my invoices through printers or ad agencies and colleagues. We had our partnership registered at the Chamber of Commerce under the name of Design Combination Saen. For me this meant, however, that I completely disappeared into anonymity.

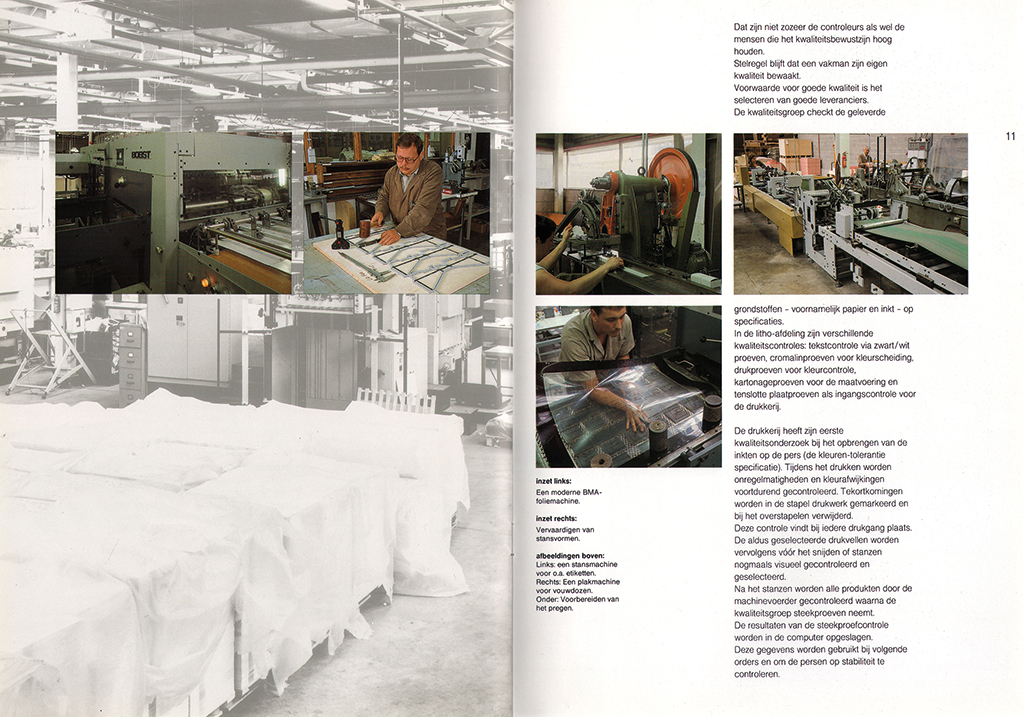

In those years, Gasunie did not have a real corporate identity program. Different designers were commissioned, who were instructed to use the official logo but received no typographic or other guidelines, about the choice of typeface for instance. This led to a proliferation of graphic expressions. I was commissioned to write a proposal and describe the minimum conditions for an identity program. After adding some examples, the proposal was printed as a small booklet that was distributed among the departments. Subsequently, I was asked to develop guidelines for additional applications, such as fleet lettering, signage systems, exhibitions, and so on. In the end, this would make it possible to create a complete house style manual. Everything had to reflect austerity.

A selection of publications, Gasunie (1970-1980).

The last straw

With the children to take care of I initially was not too bothered by the loneliness of living in the remote forested area in Drente province where we had moved to. such a remote place. I spent every spare moment behind my drawing board, because the amount of work supplied by Gasunie kept me busier than ever (I was correcting proofs even while waiting to deliver my youngest child).

I never showed my face at the company headquarters in Groningen. Everyone I worked with came to our house for meetings. Sometimes I would receive a booklet or a calendar with my name in it; in the real print run no designer would be mentioned. Gradually, this isolated anonymity started to bother me. Even more so as I got to read the letters that congratulated Mr. Visser with another wonderful publication I had made namelessly.

The low point occurred in the late 1970s. After the somewhat turbulent production of a booklet, my husband promised to invite all who had collaborated and their spouses for a dinner party. I had used photos of Dolf Kruger, whom I have known since my youth. I was looking forward to see him and his wife again (they lived in Sweden). Later I learned how wonderful the party had been. I hadn’t been invited, neither as the responsible designer, nor as Jan’s spouse. That put the lid on it. This had nothing to do with conflicting interests, this was something completely different.

There had been occasions before where Jan had kept me from attending an event if he expected me to draw more attention than him. Increasingly I had felt the need to slip off now and then. I would bring the children to my parents and visited family and friends in Amsterdam. I regularly had lunch with Wim Crouwel, for example, and we would talk extensively about our work.

But with that dinner a line was crossed. There were other issues, but above all I could no longer accept the fact that I had turned into something like my husband’s design robot. I left home, bringing my youngest children and my drawing board. I moved to Wijdenes in Friesland, near to where my parents were living.

Wiped out

My work for Gasunie continued after the divorce. Meetings had to take place in a neutral location, for which Otto Treumann offered the use of his studio.

On October 24, 1983, Gasunie’s extended identity program was finally presented to the management of all divisions. The first corporate identity of national energy supplier NV Nederlandse Gasunie was completely created by me – a woman. Over a period of eighteen years I produced some 2,000 elements. My ex-husband was commissioned to interview me for the staff magazine Gasuniek to let it be known that staff would have to deal with me for all spin-offs. However, he ignored the instructions of his boss and instead published an interview with Otto Treumann, which dealt mostly with Otto’s WW II years and only in a sideline dealt with the identity program, mentioning Otto as its chief designer.

That is how this marvelous commission, which should have been the crowning of my career, ended up among the work of another designer through the machinations of a rancourous ex-husband. I had expected some form of revenge after the divorce. I hadn’t ruled out that he would play down my efforts or even deny them. But what was really shocking to me was that everyone just seemed to accept it. Apparently they still found it hard to believe that a woman could have done this work under her own responsibility. Emancipation still had a long way to go.

In 1987, three international design organizations organized a joint congress in Amsterdam (Design 87). In the Stedelijk Museum, an exhibition about Dutch design was held as part of the manifestation Holland in Form. Two showcases were filled with my best work for Gasunie. The information said: ‘Design Otto Treumann’ even though the organizers knew better. Together with the exhibition’s curator I had completed the loan contract and I was the one who had signed it. No mention was made of the Gasunie designs in the catalogue.

Brochure for Gestel printers, Eindhoven (1987).

Logo for ‘Incest’ foundation, West-Friesland (1988).

Logo ‘Peace’ and international collaboration of the city of Hoorn and Tanzanian towns: a black fish swimming into a white world, and vice versa (1989).

Logo for council housing foundation, Harenkarspel (new municipality formed by three previously separate towns) (1991).

By chance I learned that Jan had retired from Gasunie and that they had terminated all his internal and external activities. The corporate identity program was also put to a halt, even if it was not completely finished. I was out of a job, yet I was never given notice. I knew that over time several companies had inquired who the designer was of their corporate identity program, so I asked Gasunie if they could provide me with their names. They said that such a file existed, but that Jan had taken everything with him because he was starting his own consultancy (connecting clients with designers). My work was in his portfolio with the names of other designers. No-one would notice, because my name was never mentioned in anything. I felt like I was literally wiped out – like I had never existed. I talked to Jantien Peeters at the GVN bureau, but she couldn’t help me either.

Annual reports for Tropeninstituut, Amsterdam, for Ben Bos (1989 and 1992).

Starting over

Few projects were coming my way. Nobody knew who I was and the economic situation in the Netherlands was rather deplorable in those years: not the best of times to establish a new design studio. I gave a course of lectures at the communication section of the HEAO business school in Utrecht about the relationship between clients and creatives, based on my own experience.

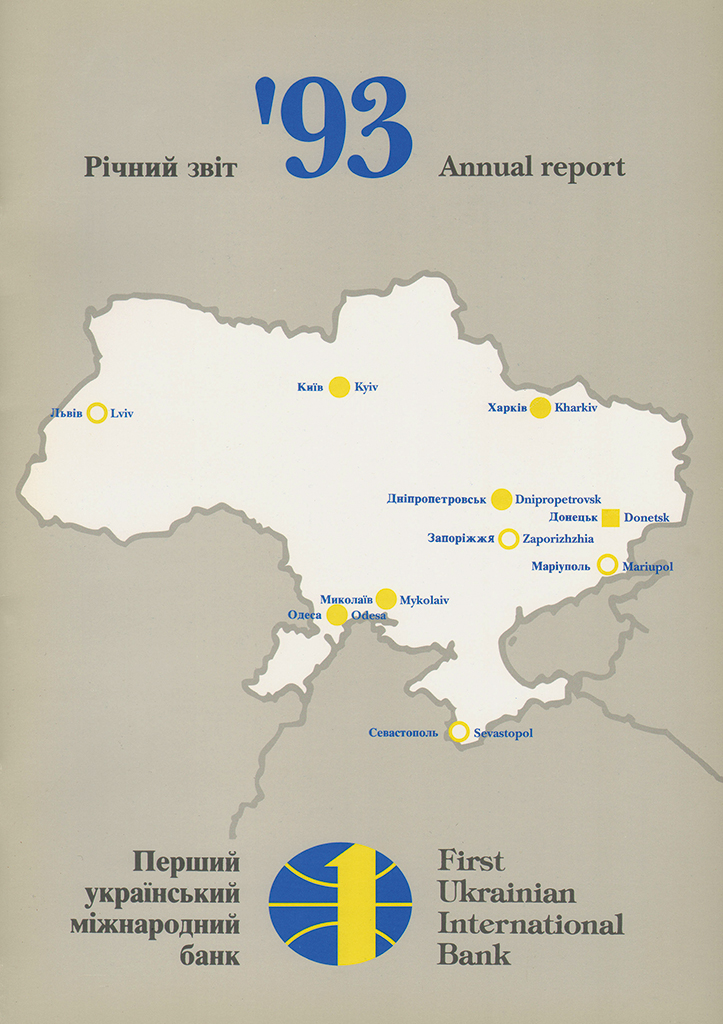

Annual report for First Ukrainian Bank, Donjetsk (1993).

Poster on the occasion of 50 years of Dutch Genealogical Association (1995).

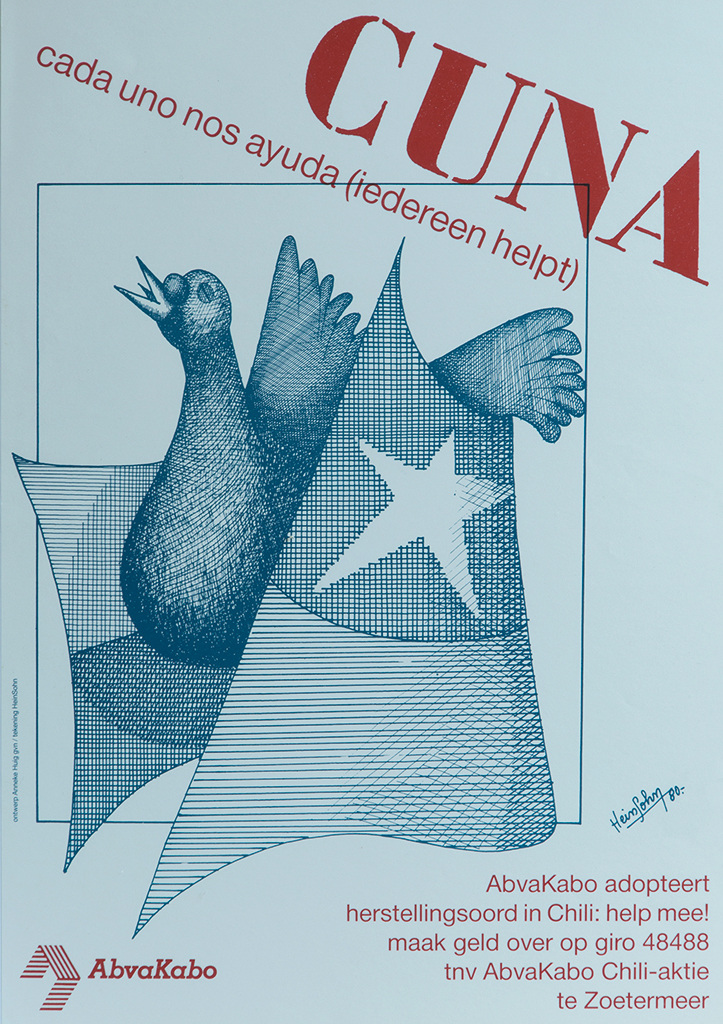

Poster for CUNA against the Pinochet regime (1994).

After two years I had finally assembled enough clients and projects to be able to stop teaching. The Amsterdam Film Museum, moved from the Stedelijk Museum to the Vondelpark, found me again. I also worked for the peace movement in West-Friesland, the CUNA project (assembling funds for victims of the Pinochet regime in Chile), a Ukraine-based bank (the design of their annual report), and a joint project of West-Friesian organizations and Tanzanian towns (a logo). It was all very international and socially motivated, but the financial rewards were poor. Through Ben Bos I did some work on identity programs from Total Design, for the Royal Tropical Institute among others. The reintroduction to my former employer TD allowed me to work with their parade horse: the Aesthedes, the first design computer. Quite an experience. The profession had certainly changed since I had worked out the sketches for Wim Crouwel’s computer alphabet.

Logo for Carrot Software (1997).

My dreams came true

Most of my dreams have actually come true. A career of 45 years, out of which 40 years as an independent designer with my own studio, always able to make a good income and to combine it with taking care of growing children. I also managed to buy my first house before I was 30. Hence, generally speaking, things turned out well for me. The only thing I regret is the slow progress of women’s emancipation.

The editors of IvKNO graduates magazine ‘40+’ at Anneke Huig’s home in Wijdenes (2001). From left: Daan Schiff, Karel Berkhout, Anneke Huig, Jef Koning. Photo: Jef Koning

Since 2007, I live in a special housing project for ecological living in Almere, near the lakes. The idealism on which it is based has brought me back to my roots. Living at the edge of the woods and with the nightingales singing during springtime, I am in an ideal environment to do some more interesting design projects. Last year I designed a logo for a neighbor’s company. Fortunately, I also have time to go to Amsterdam now and then and meet old colleagues at the Stedelijk Museum or the Special Collections of the University of Amsterdam. I have a grandson of 23 and a granddaughter of 6.

Anneke Huig

born on 16 July 1940, Amsterdam

Author of the original text: Anneke Huig, December 2014

Translation and editing in English: Ton Haak

Final editing: Sybrand Zijlstra

Portrait photo: Aatjan Renders