March 12, 1937. Ben Harsta is born in Twente, one of the eastern provinces of the Netherlands, in the village of Wierden close to the town of Almelo. The Appelhofstraat and the meadows and woods that surround the village will be his playground.

Ben Harsta: “The whole village was my playground. I discovered I could play games with the sidewalks, my friends and I built cabins in the woods, and I loved the warm sunshine in the spring as I strolled along the ditches in the grasslands. We were adventurous and discovered fish, birds, beautiful rocks and branches, even old ammunition parts or tile shards. I was one with nature and the village. At age ten, my older brother, Wim, took me to a Vincent van Gogh exhibition in Rijksmuseum Twenthe, in Enschede. Van Gogh painted subjects I recognized yet he made them look different. He had such a special eye of the world. I started to read Tolstoy and Chekov and learned that writers, too, could see things differently. Then I got interested in music, classical as well as pop. I discovered that musicians were able to transfer emotions into sound.”

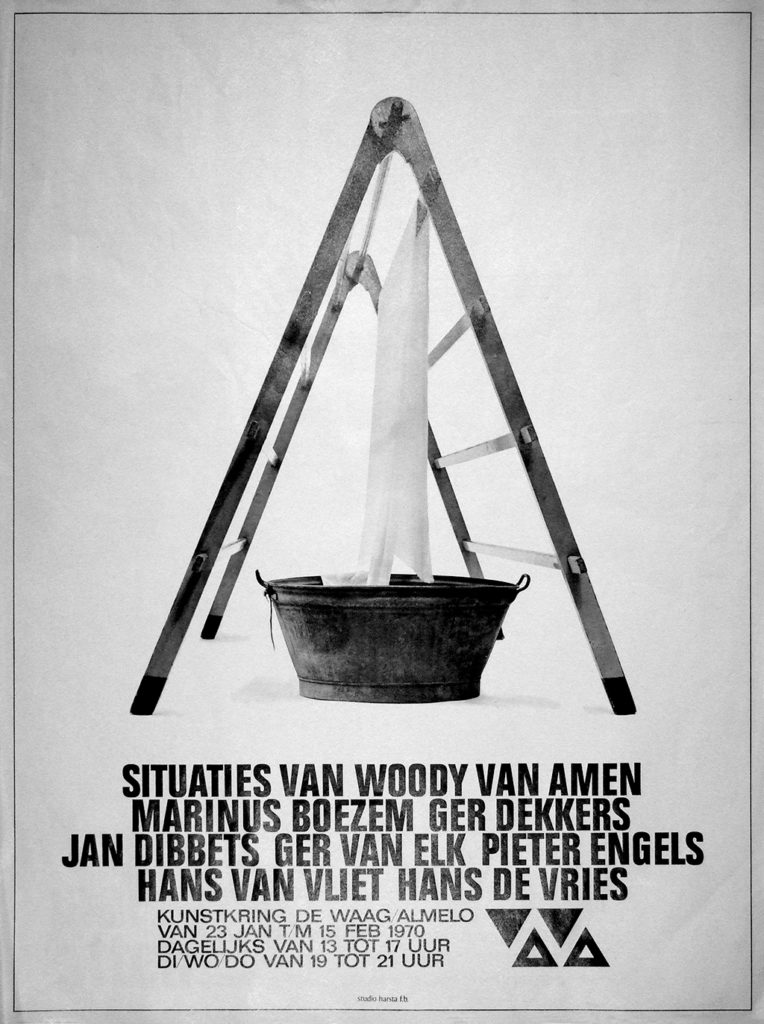

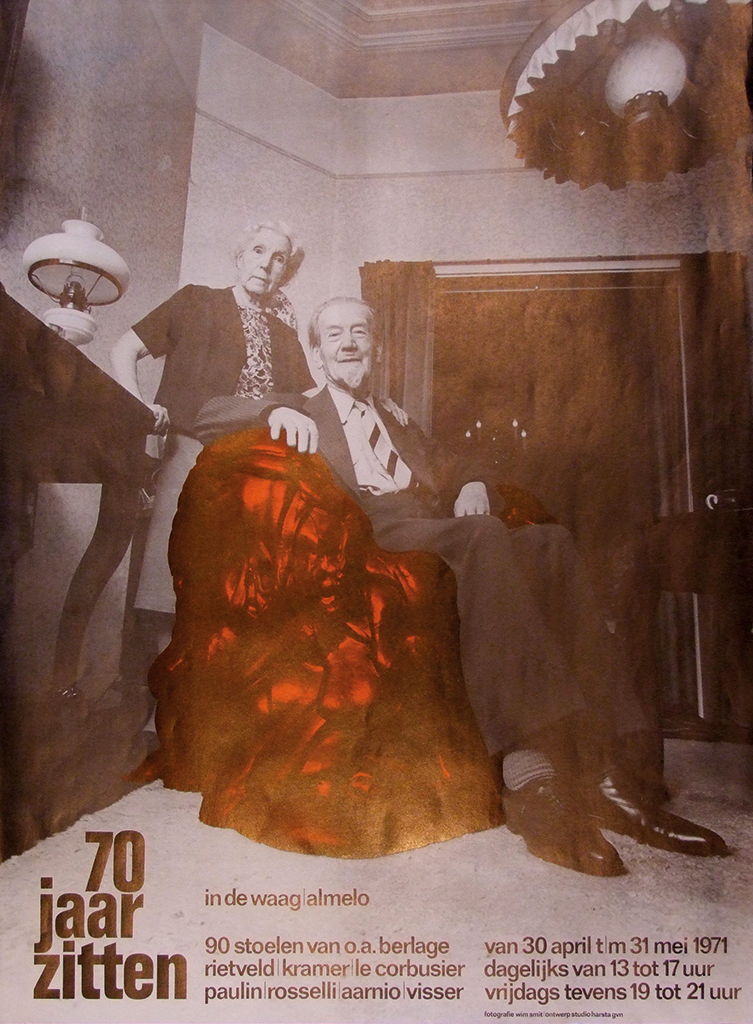

“Entering puberty, I was a timid kid without many social contacts. This isolation formed me and taught me the necessity and the power of collaboration. I was 23 before I entered the art academy in Enschede, a Johnny-come-lately but equipped with some life experience. After graduating, I explored creative hubs such as Amsterdam, Paris, Rotterdam, even Finsterwolde. I attended Peter Schat concerts, strolled around in the Stedelijk Museum and visited cultural center De Brakke Grond in Amsterdam – I explored Holland just as I had explored my village and its surroundings in my young years. Back in Twente, I became an active participant in different organizations, even a board member. I joined Rie van der Saag, our public library director, and also Jan Krol, and we worked together to realize all sort of cultural initiatives. I organized exhibitions that drew attention in ‘De Waag’ building in Almelo and produced ready-made art and graphics as well as playground designs, which were inspired by old sidewalk games I had played as a boy. I used my own creativity to draw people away from conventional patterns. I used environmental concepts just as easy as 2D designs or heated speech, to get people to communicate with others. Deconditioning was what I was aiming for and pointing people in new directions, toward more opportunities.”

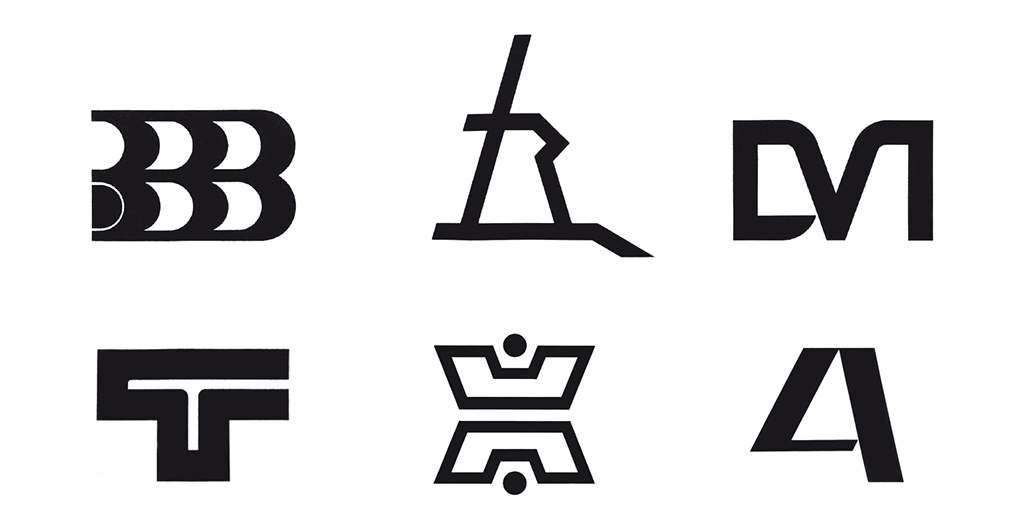

“The surrounding world inspired me, it was feeding my creativity. Graphic design and environmental design provided me with tools. It may appear that I dissipated my talents, but the ability to work in different disciplines enriched me. Now, more and more graphic designers are collaborating with other professionals. Then, I concentrated my activities on the eastern provinces because art and design were already more common good in the West, while in the East graphic design was still a vague and rather elusive phenomenon. Luckily, much has changed in Twente, even if I still do encounter rigid attitudes. Nevertheless, I am happy with what I contributed and I still enjoy being involved in projects in Hattum and the region.”

The demise of the textile industry

Until late in the nineteenth century Twente was an isolated part of the Netherlands, blocked off by the IJssel River in the West and with bad connections to the North and the South. The people had to adhere to themselves with only the textile industry providing employment. Daily life moved around the family and the neighbors, and they all worked and lived in small communities, which had their own specific culture and their own community organizations. Brass bands were a huge thing in Twente. It was the amateur who dominated culture; very few were able to become professional artists or designers.

After WW II had ended, the textile industry in Twente, able to blossom again, fueled the region’s economy and its improving cultural climate. This did not last long; in the 1960s and 1970s, the textile industry disappeared to low-wage areas in developing countries and left a desolate jobless population behind. Art and design again were far from people’s mind. The Dutch government interfered and helped Twente back on its feet by founding the technical university in Enschede and paying for the construction of the A1 freeway. With the rise of the educational level came the demands of a more diverse and lively cultural life. The national government offered a helping hand, amongst others by supporting the Enschede art academy (AKI) founded in 1950. Architects such as Pieter Blom and Jan Hoogstad were commissioned to create interesting new buildings. In 1958, a music college was established, which in 1972 became a full-blown conservatorium.

Harsta: “I was fascinated by the postwar developments in art and design such as Cobra and the Zero movement and I tried to attend most concerts, visit all museums and as many exhibitions as possible, and I read the world literature. Meanwhile, in Groningen a lively art scene was created in Finsterwolde around the farmer/gallery owner Waalkens. One of my good friends, the artist Han de Vries, even moved to Finsterwolde. I wanted to get something like that going in the Almelo region. I tried to concentrate different art initiatives in my studio and incorporate them in my own art and design.” In 1976, a group of AKI-educated artists decided to found the collective ‘De Enschedese School’ and in 1984 the first Photography Biennale took place. Cities improved their cultural policies; schools offered a better art education; designers were granted more opportunities. In 1985, Enschede got its renovated theater and in 1988 it was followed by a new music center. At the start of the twenty-first century, professional art and design in Twente had acquired a stable position.

Breakthrough

On April 19, 1969, Dagblad van het Oosten journalist Thomas Vos wrote an article about Ben Harsta’s life and work. Its publication resulted in the Twente establishment asking Harsta to join the board of the art circle ‘De Waag’. Harsta: “I met all kinds of people and I was able to forge new collaborations.” Harsta had graduated from AKI in 1964, in an environment where at the time art and design were seen as one and the same profession. Nevertheless, design colleagues from the more advanced West, assembled in the professional association GVN, asked Harsta and his assistant Wim Slothouber to design their newsletter. They presented an unconventional design that established their name in the profession but was never printed. Harsta: “Even after the cultural climate was changing, many potential clients in Twente hesitated to commission a designer from Twente. They preferred to play safe and engage designers of name from the West. As a board member of several organizations I was able to change opinions and move projects in the direction of our local professionals.” Harsta’s convivial and social skills were appreciated; he never tired of devoting his time and expertise to committees, workgroups, foundations, and other cultural organizations.

Ben’s wife Marlene Harsta: “After 45 years of marriage I’d describe Ben as hot-tempered, authoritarian, vain, hard-headed… a Friesian, rather. But he’s an idealist, too, a progressive thinker, artistically inspired, sociable, a man from the Left. Conviviality is in his genes, and design is what he learned: a way to make money that allowed him to express his feelings and realize his ideals. He is driven, and overly enthusiastic to present his concepts and designs. He has no need for criticism – he thinks he is always right. He may have entered his seventies, but his alertness hasn’t disappeared and he continues to put forward new plans. Now and then, his relentless energy exhausts me: I’d like to have a day off, without having to respond to his creativity. But his interest in his fellow human beings never ceases, his loyalty is legendary. His most important accomplishment? A few years ago he renounced alcohol and as a result lost a lot of weight.”

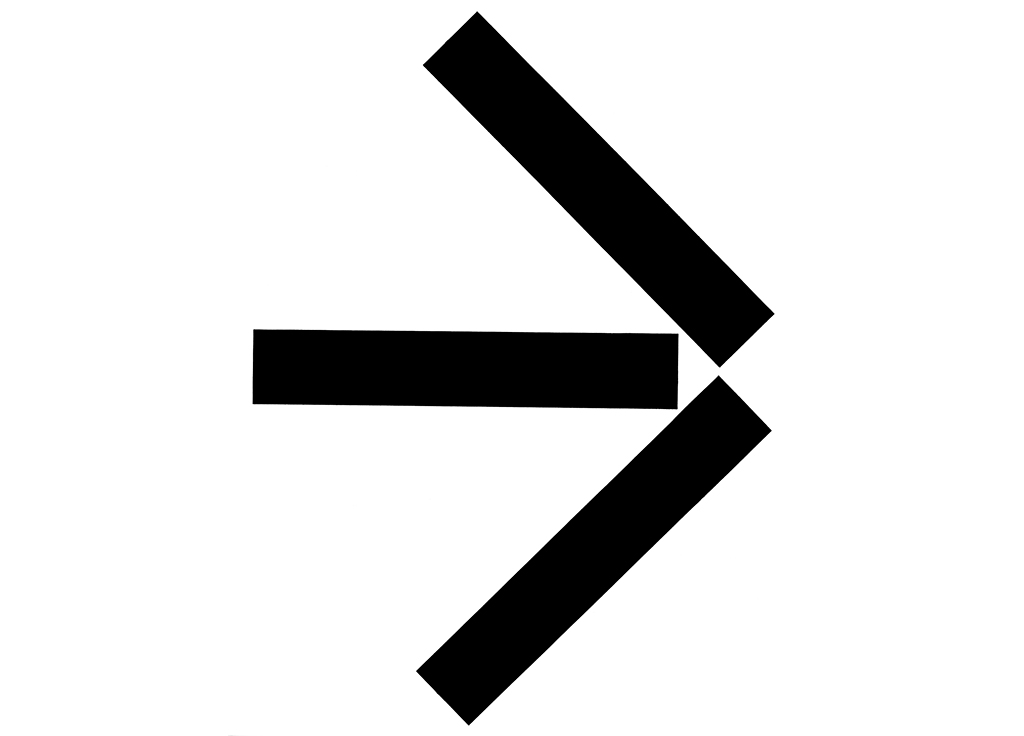

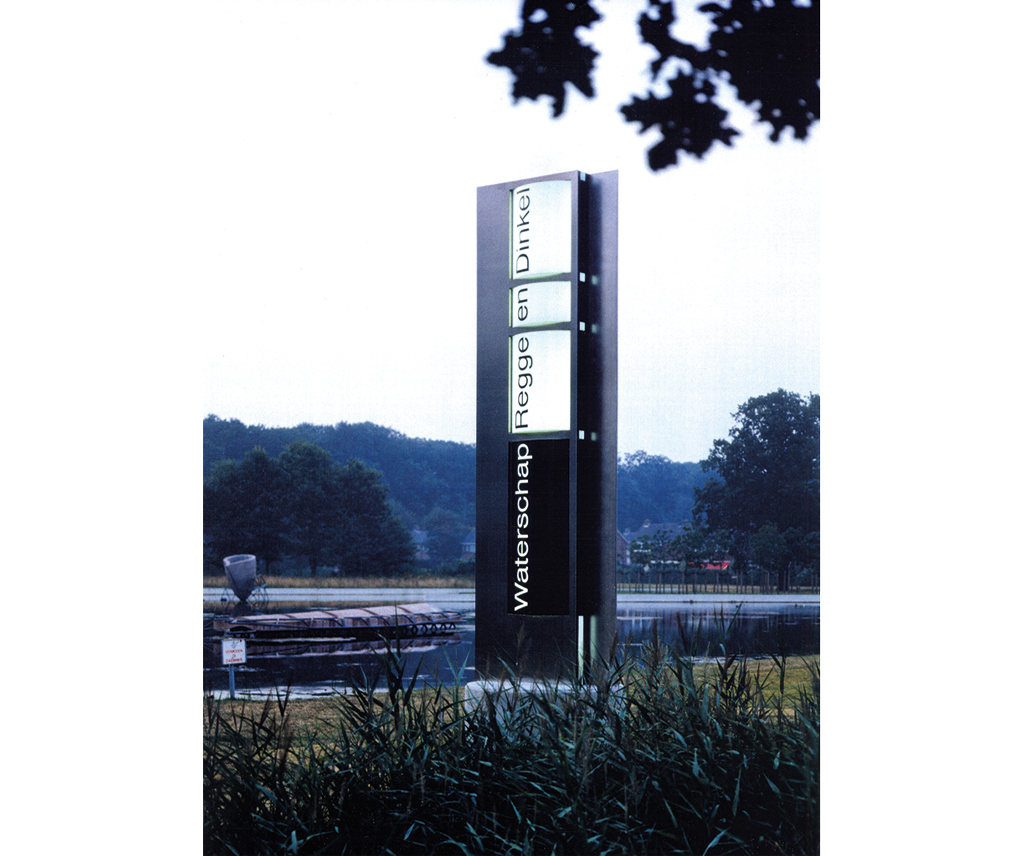

From 1986 to 2002, Ben Harsta worked with Remco Crouwel in their partnership Harsta Crouwel BNO. Remco Crouwel: “After graduating from AKI, I noticed ‘Ben’s arrow’, an intriguing design. I decided to contact its creator and we hit it off and decided to form a partnership. I learned to know Ben as an outspoken guy who picked up everything with a never-ending enthusiasm and commitment. He’s not just a graphic designer, he is a conceptualist who always believed the work was practically done once the rough lines were decided upon. That’s when I had to step forward and take care of the details. We could clash: because I would decide that the concept needed to be more in the background, while Ben was adamant that the concept had to be succinctly visible in the design. Ben is a much more sociable person than I am; he went out and talked to everyone; meanwhile I remained in our studio to give direction to our team. Ben is not just convinced he is always right, he is often right, but he isn’t always the greatest of diplomats. He doesn’t shy away from pointing out that his opponents, whether his clients or the chairs of boards he is dealing with, are wrong. Ben couldn’t always understand why they had trouble with accepting his vision or opinion. Our own heated discussions strengthened our relationship. Ben is a generalist. He created 2-D or 3-D concepts, he made theater and sometimes he mixed his proposals with politically hot elements, which could produce surprising results. Ben could drive me crazy if, just before we had to present a proposal, he would change or add something he had decided that ‘was essential after all’. Nevertheless, we were able to produce wonderful designs; the identity program we designed for the Naturalis museum in Leiden was a milestone. However different we were, we made a strong team.”

Over time, Ben Harsta created many 3-D concepts. In 1968, his Spirantijn fountain design was installed in one of the city of Zwolle’s canals; in 1969, his design for an ‘art-critique-column’ made it into national newspapers; in 2002, he presented a plan for a cultural-historical landscape park along the canal that connects Almelo and Nordhorn; and in 2009, in collaboration with landscape architect André Bijkerk, he designed the adventurous environment of a playground at one of the Brede schools (‘Eninver’) in Almelo.

Great ideas, small budgets

Henrike Nijman is the director of Brede district schools: three elementary schools and a network of organizations benefiting children younger than age twelve. Its goal is to protect children from negative influences and to invite them to be creative. Henrike Nijman: “Ben is one of those people who are able to think out of the box and to allow his creativity to roam. We commissioned Ben to design, in collaboration with André Bijkerk, a creative playground. We soon discovered that Ben would think big and let his ideas grow during the project’s progress until they were bigger than the available budget allowed. We had to rein him in, which he didn’t like very much. He didn’t care much for government restrictions with regard to children’s playgrounds either. I had a hard time to convince him we had to abide to the rules. But he was open to the involvement of parents and made use of their suggestions. He inspired us all. His expertise, his knowledge of materials, and his boundless creativity guaranteed a result that is really satisfying. He worked with green zones and water and recycled components. As his client, you have to know very well what you want; and you have to harness yourself to withstand Ben’s boundless energy at trying to convince you of your wrong.”

Ben Harsta’s own homes give testimony of his love of architecture. His son Atto was an intern at Twente-born Frido van Nieuwamerongen’s architecture studio Arconiko, in Rotterdam. Arconiko designed two of the Harsta homes, the first one a redesign of an old warehouse in Almelo (a certified monument), and the second one a ‘reanimation’ project in Hattum. Van Nieuwamerongen: “It is great to work with some like Ben. Driven as he is, he refused to give in to the restrictions his budget demanded and he didn’t allow any concessions in the design. Ben isn’t the typical reserved provincial; he really goes after his goals. I first met Ben in 1995 through his son, who was an intern at our studio. I learned quickly he is a conceptualist and able to attract people to join his vision, whether it’s about a 2-D or a 3-D project, or a political issue, or something happening in the street or in a theater. Clients have a hard time trying to turn him around and change his opinion. But he is flexible when dealing with designers he respects. I love working with Ben. Even if he is impatient: a concept doesn’t get the opportunity to ripen, or even lay around for very long – the project always has to move forward.”

A newcomer to Hattum, Ben didn’t hesitate to make new acquaintances or to get involved in local discussions and projects quickly. “He is a social person, maybe a do-gooder,” adds Van Nieuwamerongen. “Anything culturally interesting has his passion and anything having to do with design challenges him. Luckily his wife is able to rein him in at the times that his creativity takes a too unrealistic flight.”

Transformation

In the 1960s, Enschede awakened, but Ben Harsta went elsewhere for inspiration. It took him five explorative years before he could apply his ideas in his old community. In 1969, he started a series of acclaimed exhibitions in ‘De Waag’ in Almelo. In 1972, he joined a group of Almelo artists (BAK) and from then on he had a finger in the city’s cultural pie. He was already an active member of the socialist party (PvdA) and worked hard, together with the public library director Rie van der Saag, to improve the region’s cultural climate. By the 1980s, a lot had been accomplished for art in Overijssel; it had become understood that art had a financial component and was worth investing in. Harsta Crouwel, too, was doing well and was asked frequently to do national design projects. Harsta: “Today, the problem is that the financial-economic side of art is receiving too much attention. This can lead to blurring, to loss of sight of what it’s really all about.”

From a timid man coming from a traditional society, Ben Harsta developed into a man of social feeling and an emotional person, caring about others. He worked hard to lose his timidity and come out of his social isolation because he desperately wanted to collaborate with other people. He became a man to reckon with: his imposing stature, his motivation, his integrity, expertise, and creativity, as well as his dominance in social contacts and his endless enthusiasm and boundless energy could indeed help make changes. Art and design were the fields that provided him with the tools. Ben Harsta wanted Twente to follow in the footsteps of the western part of the Netherlands, where the 1960s had already been greatly influenced by new thoughts and behaviorisms.

Harsta: “Without giving up all of the traditional way of life in Twente. I just wanted to stimulate an open eye to what was happening elsewhere in the world.” He started in Almelo, where he ‘penetrated’ the city council, which at the time had no clue what the importance of a cultural or even a recreational policy was. Harsta was a crusader. Meanwhile, his studio prospered. Ben Harsta: “Sixteen years of partnership with Remco Crouwel broadened the horizon and deepened the quality of our graphic designs. I learned to know Remco as a great professional and a wonderful human being. We still work together on incidental projects.” Now, the design in Overijssel can compete with the West. Ben Harsta therefore thinks it is regrettable that many clients still favor to work with designers from the West who have a national reputation. He is still fighting for more recognition of Gelderland and Overijssel designers. “They deserve to work outside the region.”

Ben Harsta managed to be of enormous importance to the development of art and design in the eastern part of the Netherlands. He was lucky, he admits, that in the years during which he was most active in Twente, the Dutch government became more aware of the existence of Twente and the importance of its cultural life and started to support its development. In 2011, Twente was no longer the western province’s poor cousin. The province of Overijssel was even eager to invest more in culture and quality. Ben Harsta had made people look and learn; he provided opportunities – he helped give Twente self-respect, dignity and a prestigious face.

Ben Harsta wished to name the people who played an important role in his life and career and helped him make Twente great: Henk Jukkema / Wim Slothouber / Peter Elbertse, Henk Ossewaarde and Marien Stoel / Marcel Hein / Jet Krüger / Greetje Steffens / Hans Hendriks / Maaarten Bos, Jan van Elsberg, Marja Rutgers, Ireen de Kok en Wim Rombouts / André Bijkerk, Meint Bosma, Bas Slatman / Agnes Meijer / Annie and Ben Hoekman / Adriande Uspessy and Filiep Manger / Ben Eijs / Marlene Harsta.

Ben Harsta

born on 12 march 1937, Wierden

Author of the original text: Jan W. Groot, March 2011

Translation and editing in English: Ton Haak

Final editing: Sybrand Zijlstra

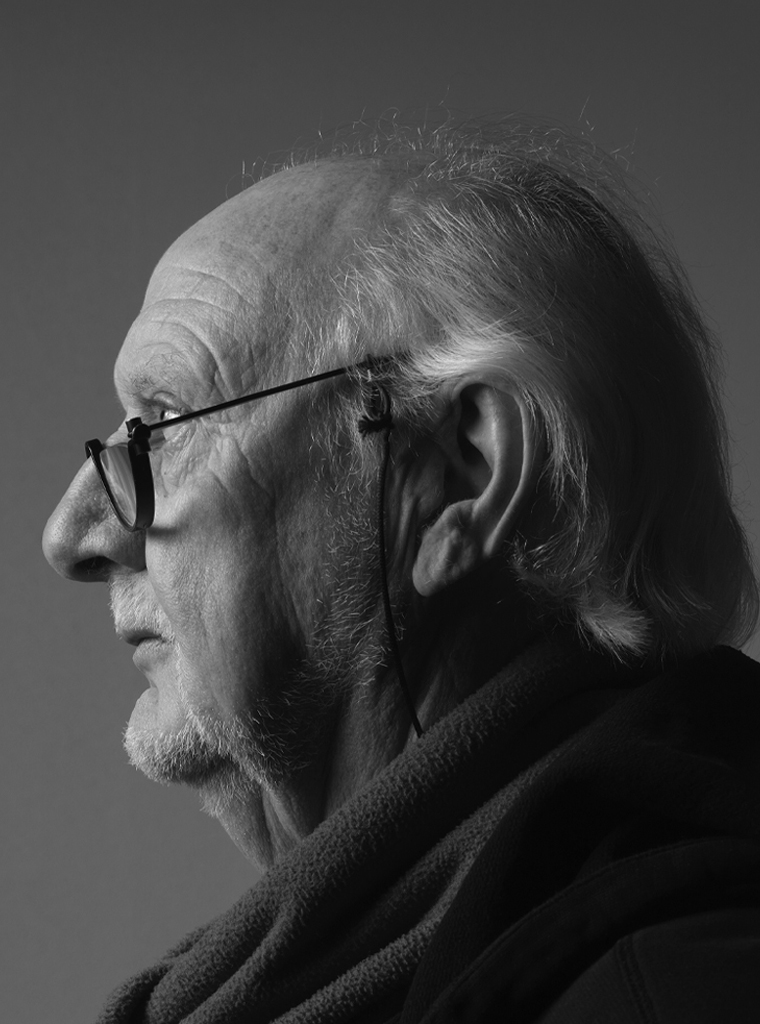

Portrait photo: Aatjan Renders