Heart Beat (2006) was Daphne van Peski’s last book design, a commission from her artist friend Carel Balth. “My 65th birthday marked the end of the flood of design projects that came to me. We were spending already much of our time in France. All of our attention was given to the home that my husband Fred Ros, also a graphic designer, and I were building in Villecroze near Salernes. An austere, modern design by a young Belgian architect we discovered by chance in the area, Grégoire Semal. He had designed his father’s house and we loved its remarkable use of windows. We called our home Villa Olea for the hundreds of olive trees on our land; these will keep us busy for years to come.”

Daphne van Peski was born in Geneva in 1942. Her first education was in French. Van Peski was her mother’s family name, which came from Pestchansky, a name with origins in West-Russia that can be traced back to the seventeenth century. She never worked under the name Van Peski. At Total Design, the secretary had entered the last name of her then husband, Ben Duijvelshoff, on TD’s stationary and Duijvelshoff she would remain.

For her first six years she lived with her mother Ingrid van Peski in Ascona, southern Switzerland, where Ingrid was a member of a circle of young people, all full of ideals. There, high on Monte Verita, her mother had befriended an architecture student. Daphne was born from that relationship. “The first time I met my father I was about forty. A dear man. Since then I visited him regularly and got to know him very well.” At the time, Godi Cordes ran an architectural studio in Zug, Switzerland. He was excited to learn he had a daughter who worked in a creative profession he could relate to. “It turned out we shared many interests.”

After six years, Ingrid decided that Daphne should continue her education in Holland. They arrived shortly after WW II and found a home in Sassenheim, quite a contrast with the mountainous area of Monte Verita. “My mother was one of a kind. She painted and would continue to paint all her life. White doves would circle in her large studio in Sassenheim.” At the local public school that offered a traditional education, Daphne found the structure she needed to build up her life in Holland, after she had failed to do so at the Oegstgeest Montessori School. Within three months, she became fluent in Dutch; she adjusted well to life in the Netherlands. At home, Ingrid and Daphne still continued to communicate mostly in French. Her proficiency of the French language got a boost when, in her ninth year, she was sent to Switzerland for a couple of months. She would make good use of her knowledge of the French language later, when Total Design had French clients.

She received her secondary education at an all-girls school in Driebergen and at the International Quaker School at Beverweerd Castle near Werkhoven. Dirk Jan van Haren Noman, a future co-director at TD, was one of her schoolmates. The humanities attracted her, introducing her to art and art history. Eventually, she successfully applied for admission to the Amsterdam art and crafts school, IvKNO, where she presented a portfolio with work created at the Quaker School. She fit in well and in her third year took typography, surrounded by the old type cabinets from teachers Charles Jongejans and Melle Oldeboerrigter, who taught her to set lead type, especially paying close attention to spacing. More importantly, perhaps, they taught their students important life lessons, too.

After graduating, Daphne’s first commission as a freelancer was the design of a commemoration book on the occasion of 50 years of Landbouwhogeschool Wageningen. “It was too much, too big a project for me to handle.” But the book got printed and the young professional had learned a lesson or two. “At school they didn’t teach us things like communicating with clients. We had to learn in practice.”

Before becoming a freelance designer, Daphne had applied for a job at Total Design. She wasn’t accepted because she had no previous work experience. Her neighbor and friend Jan Holsbergen introduced her to Studio DDM (Douwes, Douwes & Meijer). Her first job. “I used to joke about the coffee I had to make and the trash cans I had to empty. They primarily designed packaging, for tulips bulbs and what-not. My first project was a matchbox label. I left DDM after eighteen months.”

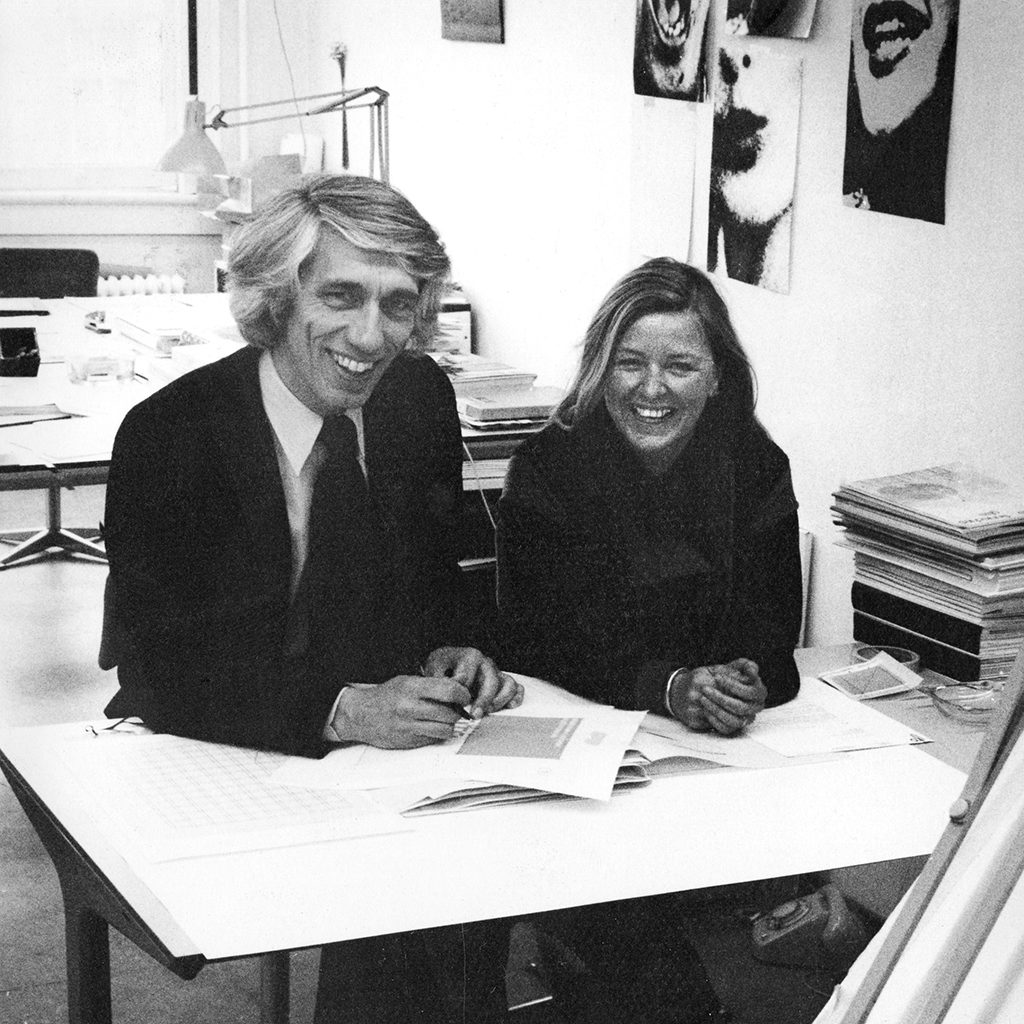

She finally managed to get a job at Total Design and ended up in the team managed by Ben Bos. “Ben was a born teacher. He gave me serious jobs to do and looked over my shoulder, never pushy, always inspiring.” At first, she experienced her team membership as a continuation of her schooling. “I am so glad I was in Ben’s team first, before I was asked to join Wim Crouwel.”

They worked for Randstad, among others, following the guidelines given in its corporate identity manual. “In the year Ben Bos was designing De Gruyter’s corporate identity, he didn’t have much time to pay attention to Randstad. That was my lucky break. I had to deal with the client and I learned much from the process. I became more confident and flexible. Ben let me design a small book for the Nederlandse Kunststichting (National art foundation) and he gave me a lot of freedom.” It was the beginning of a long collaboration with this foundation and its director, Henk Visser.

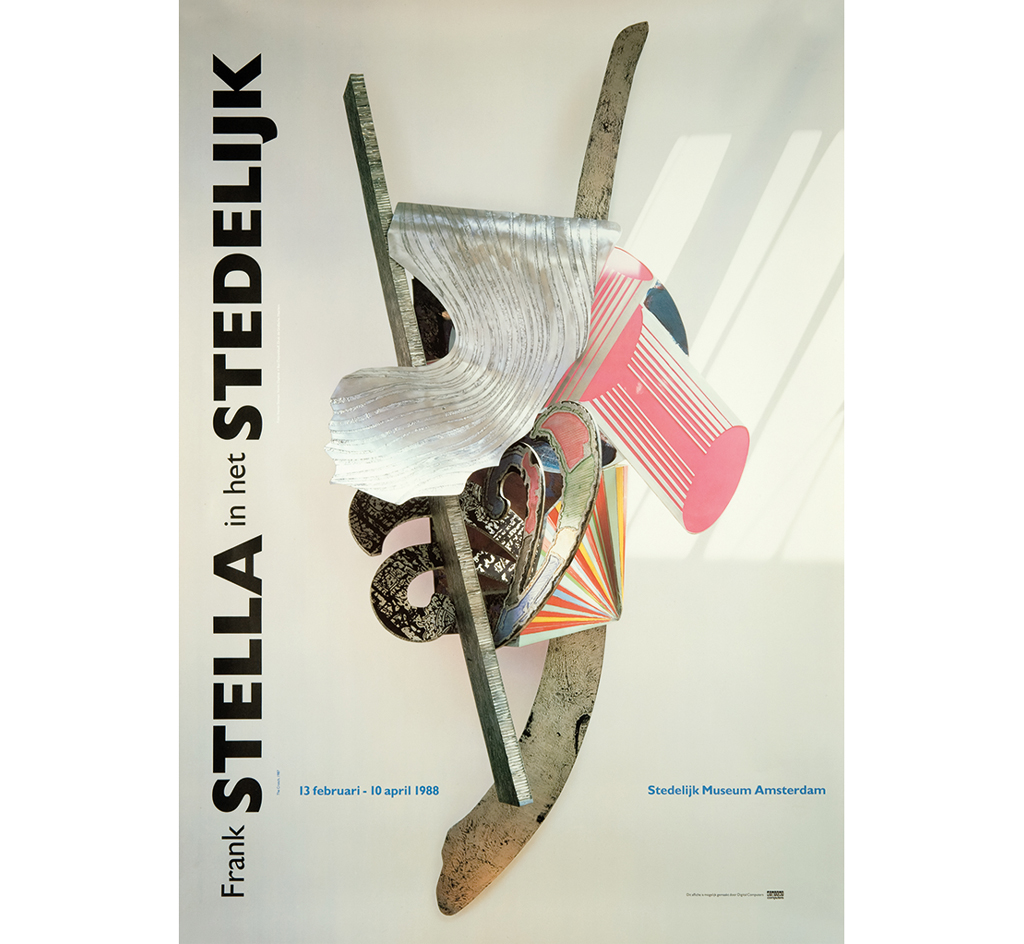

When Ben Bos could fully focus on his team again, Daphne decided she did not want to stay in her old position and wanted to quit TD. Wim Crouwel learned about her decision and did not want her to leave. He invited Daphne to join his own team, which at the time created many catalogs for Amsterdam’s Stedelijk Museum. Daphne was directly appointed to work on them. Formats, grid, and type (Univers) were a given, but outside of that there was a lot of freedom.

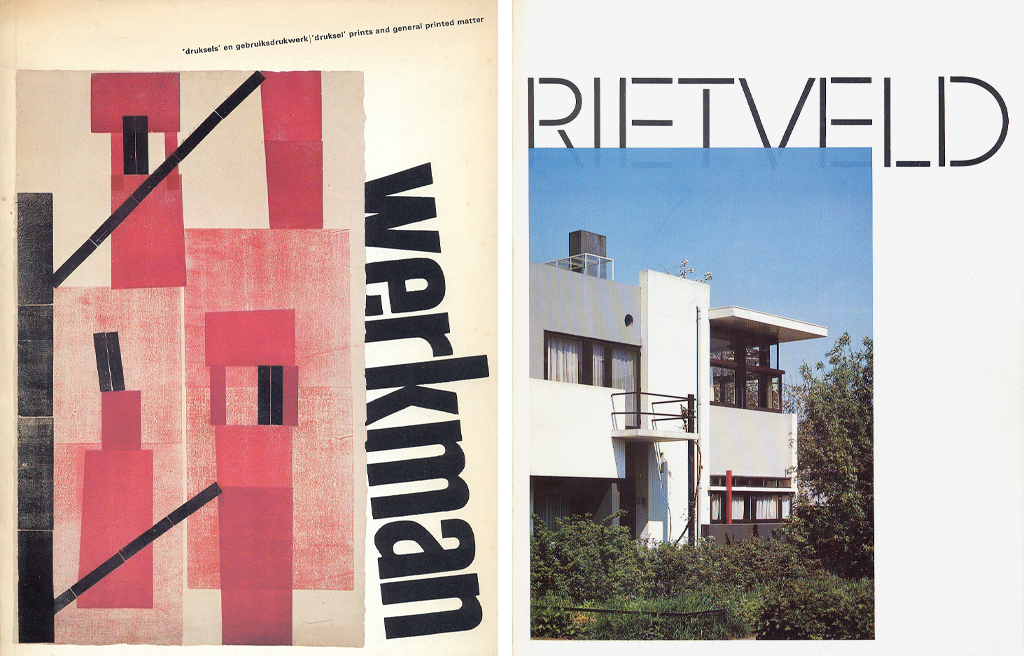

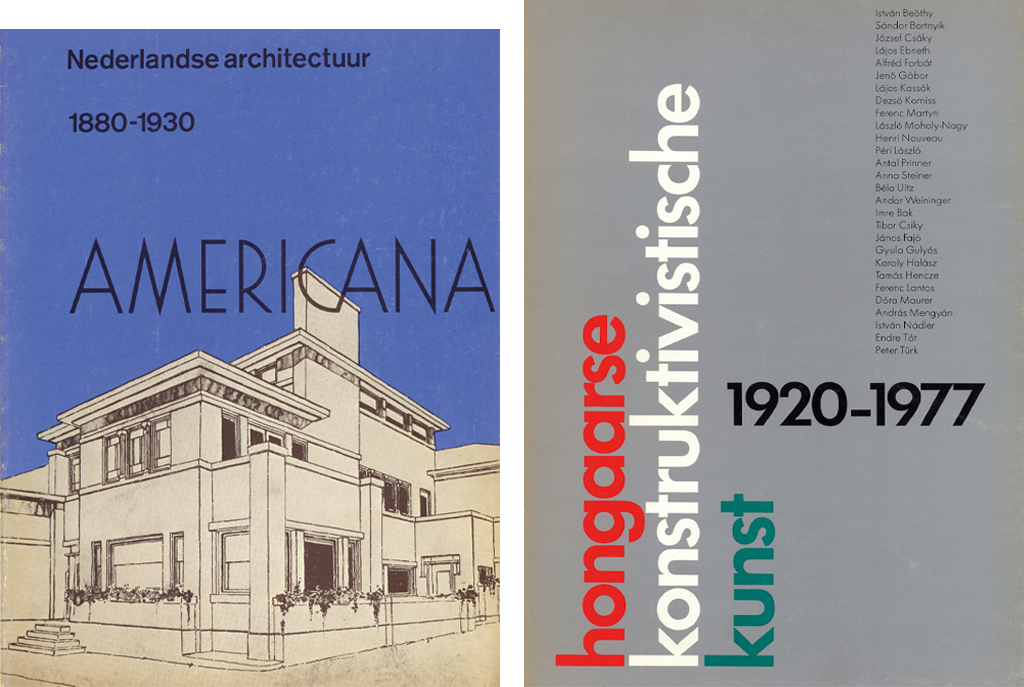

“I was happy, content. I was still in my twenties and Wim dragged me along to everything and introduced me at the museum. That was the sensible thing to do because he had just accepted his associate-professorship in Delft and did not have enough time to attend to all the details himself.” As from 1972, Daphne also worked on projects such as a series of publications about Dutch architecture (Nederlandse Architectuur), the redesign of the old Groninger Museum, and publications and promotions of Nederlandse Kunststichting and Holland Festival. “Wim was very generous, he gave me all the space I needed to continue my development as a designer.” In 1972 Daphne was accepted as a member of the GVN, the Dutch association of graphic designers.

An important TD client was the Peter Stuyvesant Foundation founded by tobacco mogul Alexander Orlow. On a regular basis, Orlow would ask Wim Crouwel to re-hang his art collection in Turmac headquarters in Amsterdam and in the cigarette factory in Zevenaar. “One day, Wim asked me to take over from him because he didn’t have time. I came with a proposal, he looked it over and OK’d it. But Orlow immediately noticed that it could not have been Wim’s work. I had assigned a key piece to the wrong spot, something Wim Crouwel would never have done. Wim admitted to Orlow he hadn’t had the time and that he was going to fix it. He defused the situation, he was good at that.”

In the 1960s, Total Design had become the most important design agency in the Netherlands, but in the 1970s the competition grew explosively. In The Hague there was Tel Design with Gert Dumbar, whose work was more free and colorful compared to the TD’s ‘dogmatism’. “I am convinced this played a role when TD decided to attract designers with another vision. In 1976, Jurriaan Schrofer came to enforce the team, followed by Anthon Beeke. This kicked everybody awake. Anthon did exactly what he wanted. Many of my colleagues resented that. He would come to work at an hour when they were just leaving for home and he was often late with his presentations. But when the design was there it was there, and how! I worked with Anthon in 1977 for Holland Festival. Anthon and Wim designed the posters, I handled the catalog. It was a fun time when he worked at TD. He is a great designer and I like him a lot.”

Still, their critics continued to see Total Design as representatives of a design philosophy that was too dogmatic, who forced their esthetic preferences on the public. “I didn’t agree with Piet Schreuders when he expressed his dislike of TD as a ‘religion’ by destroying one of Wim’s posters, in 1977 it was, at the Rietveld Academy. I was in the audience and I was shocked. You shouldn’t do this with someone else’s creative work. Later, Renate Rubinstein wrote in Vrij Nederland about ‘the new ugliness’ while critiquing the PTT phonebook design. I didn’t agree with her either. Obviously, we discussed this inside TD. You know, there were so many different teams within TD. The outside world recognized only Wim Crouwel, but Anthon Beeke and also Paul Mijksenaar represented a much wider scope. Maybe people like them should have been asked to join at a much earlier stage.”

DEV, the esthetic design department of the Dutch postal service PTT, asked Daphne to create two of the four traditional Summer Stamps. She chose two remarkable Dutch women as the subject, Anna Maria van Schuurman and Belle van Zuylen. To the Belle van Zuylen design she added the quotation: “I have no talent for subservience,” which was not accepted by PTT’s director-general Lehman, because the previous year the theme had been the Year of the Woman. Daphne immediately proposed an alternative quotation: “To read and to write really changes the human existence,” which was accepted. She was too overwhelmed to defend her first proposal. Ootje Oxenaar, head of DEV, afterwards told her she should have diplomatically kept her silence, as he had done.

Next, a TD project for the Amazone foundation automatically came to Daphne’s desk. Via Amazone, Daphne became involved with the women’s lib movement. “At times they would irritate me. I worked hard to remain standing in a men’s world. Things aren’t always black and white. It is too easy to just kick against the male-dominated world and scream: we don’t get any opportunities! Because it isn’t true.”

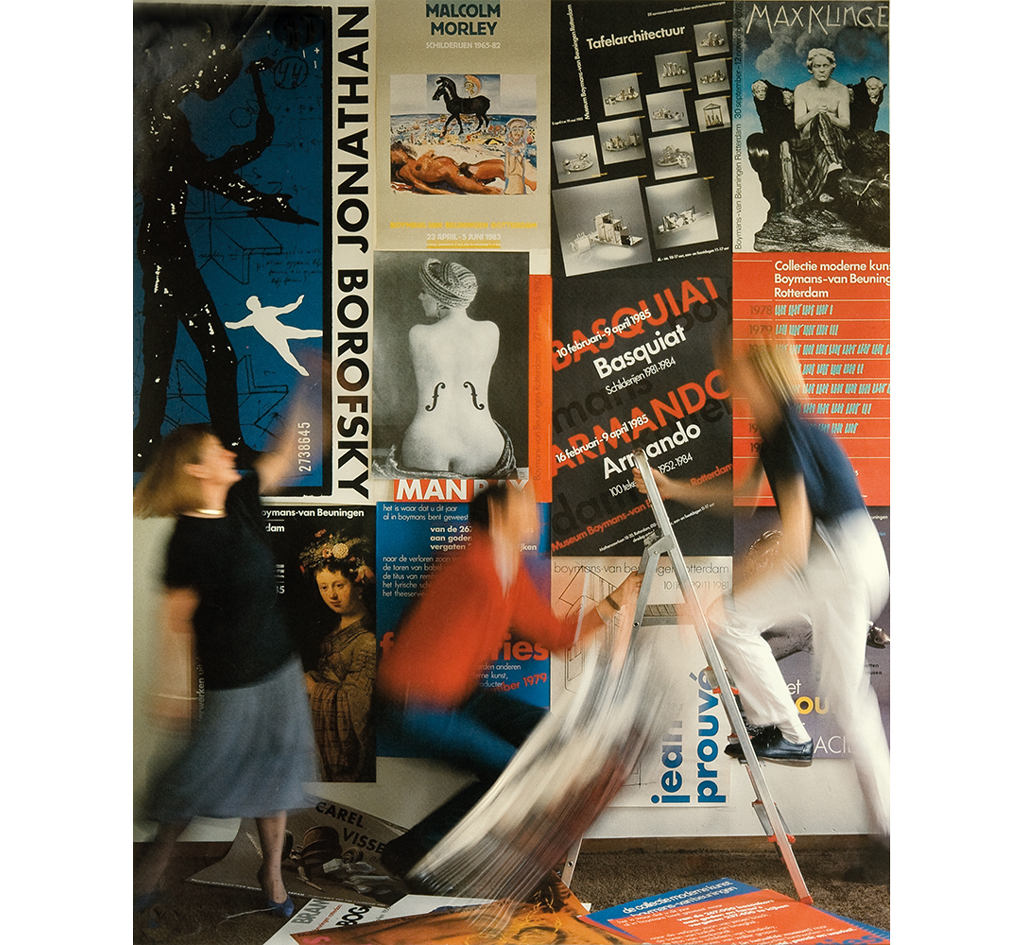

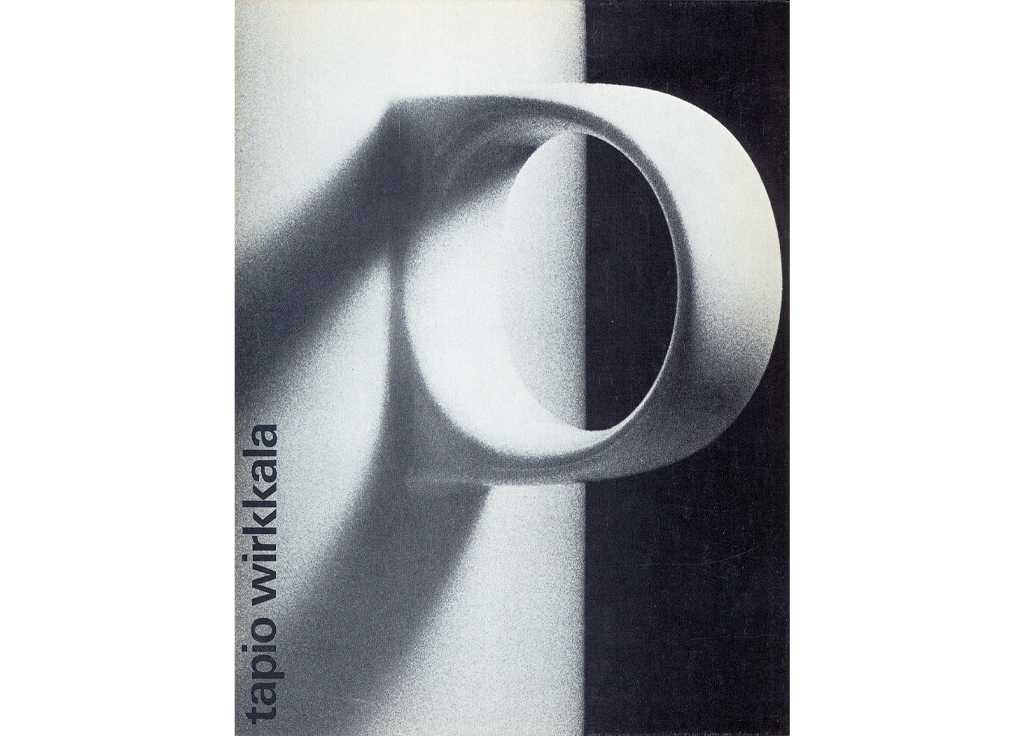

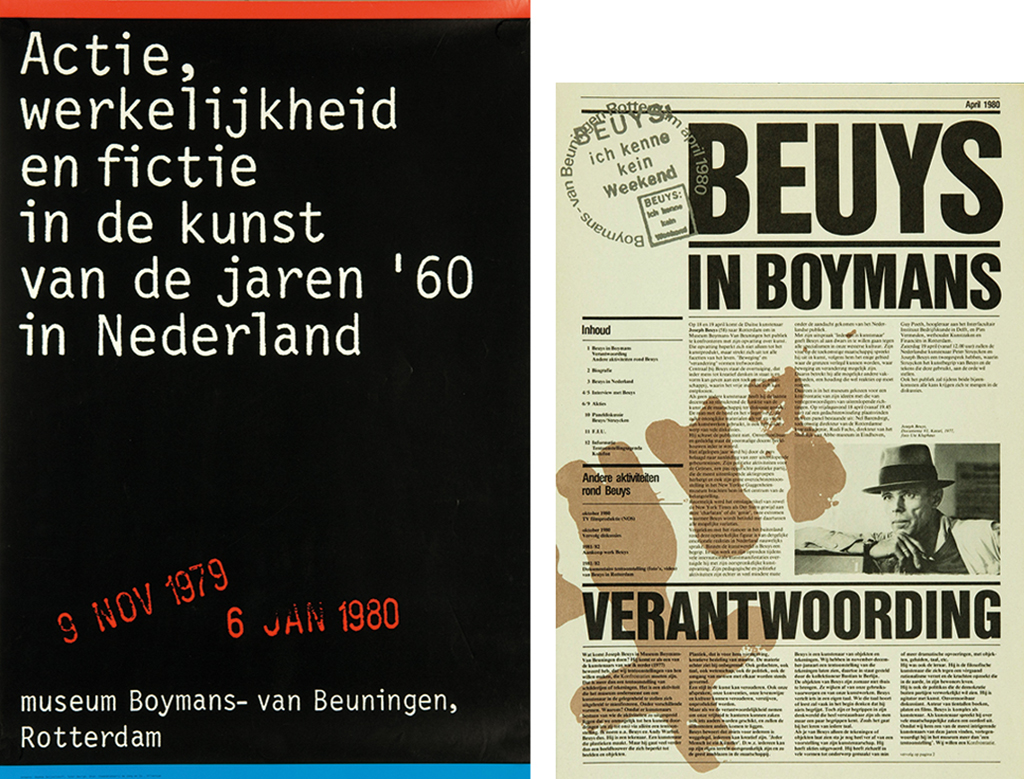

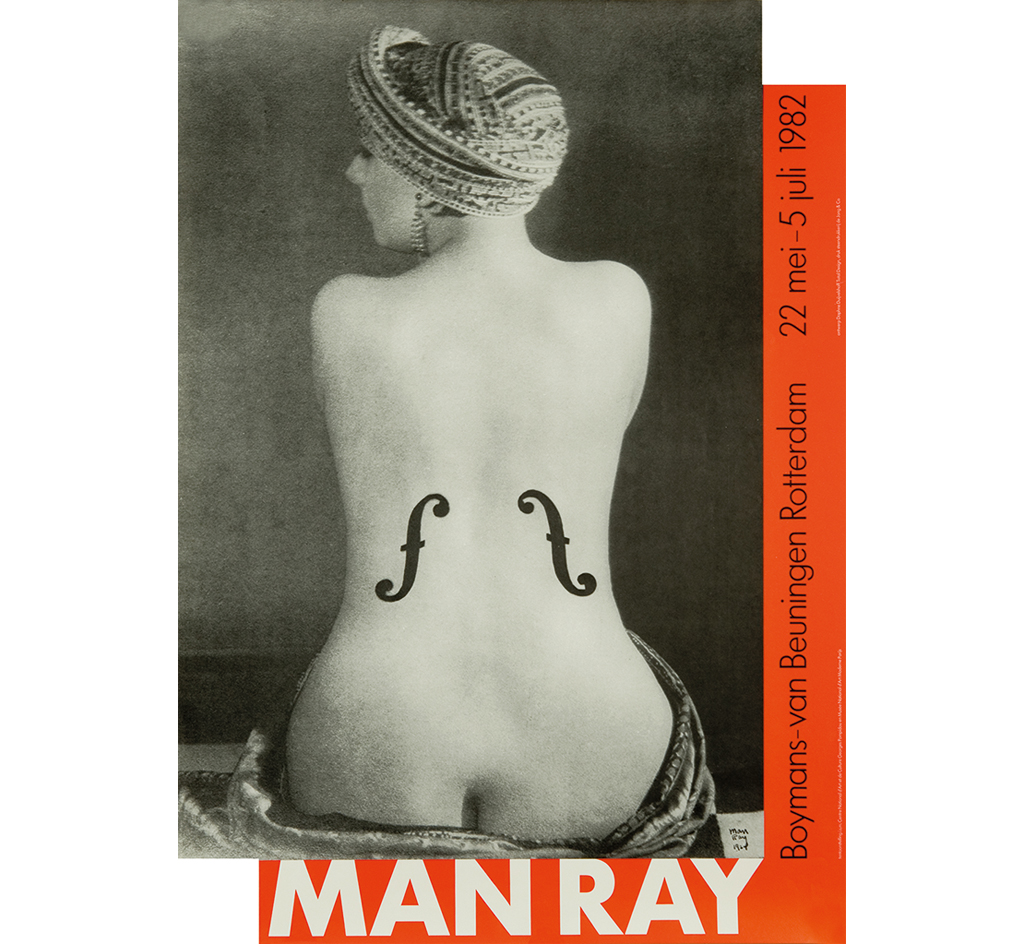

Her colleague Jolijn van der Wouw already had her own design team at TD when Daphne was still working for Ben Bos. Daphne respected Jolijn very much, and vice versa. After seven years in Wim Crouwel’s team, Daphne went on to lead her own design team. “To Wim’s credit, two women from his team got the opportunity to start their own team.” The decision was prompted by the fact that Wim Crouwel did not find it appropriate to work at the same time for the Stedelijk Museum and for Museum Boijmans-van Beuningen, where former Stedelijk Museum curator Wim Beeren had been appointed director. In 1978, as a test, Daphne designed the acquisition catalog of Museum Boijmans-van Beuningen covering the whole Ebbinge Wubben and Hammacher period. Subsequently, she stopped working for the Stedelijk and had great years collaborating with Wim Beeren. He would become her most appreciated client, someone who always kept her on her toes.

Actie, werkelijkheid en fictie in de kunst van de jaren ’60 in Nederland (Action, fiction and reality in 1960s art in the Netherlands) was the first grand exhibition for which Daphne designed the catalog and graphics. This started her collaboration with Marijke van der Wijst, who was responsible for the exhibition design. “Marijke and I had no problem with establishing our boundaries. We discussed our input and we respected our territories. Of course we influenced each other. And we became good friends.” Daphne also closely collaborated with Frits Becht, for his Intomart projects as well as his private art collection; with Jacques Stienstra, director of Brabant real estate company Soetelieve; and with Vincent Eijsvoogel, the director of the central laboratory of the blood transfusion service CLB. “Strong personalities, all of them. People who knew what they wanted. They provoked you, challenged you: you can do better. Sometimes it can be annoying, but you see the results. Parry and thrust – it’s a good process.”

During her farewell party at Total Design, Daphne described her collaboration with Eijsvoogel as follows: “Nothing is more stimulating than a critically observant and straightforward client, who pushes the designer to aim for the highest level of his or her creative capabilities.” She was speaking for the members of her team, too, in this case Reynoud Homan and Marion van der Lee.

“At the time I got my own team, Jurriaan Schrofer was leaving TD to become the director of the Arnhem academy of art. He passed me his clients. For a while this worked well, but many had come to TD because they specifically wanted to work with Jurriaan. After some time, those relationships were terminated. This was typical for Total Design: when a ‘neutral’ project came in we would see who was available and most suitable. Then there were also commissions that came in for a specific designer who was favored by a client.”

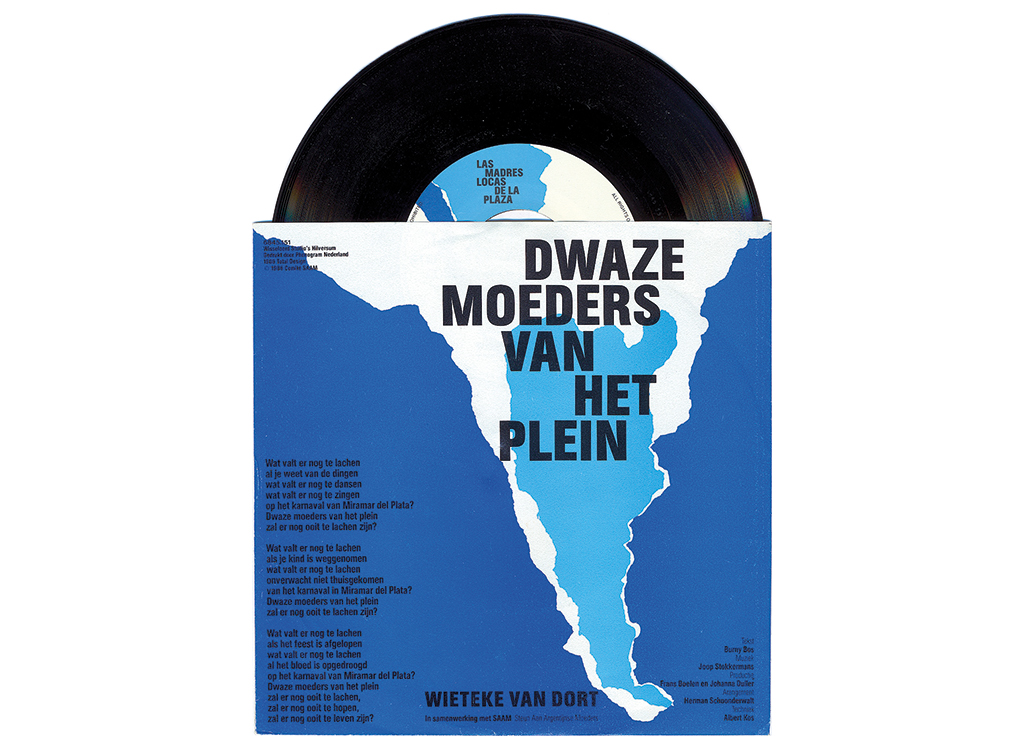

After having proven to be able to generate new business with her team and contribute to earnings, Daphne became a member of TD’s five-headed board. As deputy-director she carried responsibility for human resources. “Earlier, I had taken it upon myself to handle apprenticeships and internships, which I strongly favored because I had so missed that in the beginning of my own career.” In the same year, Daphne started to work without pay for SAAM, the foundation that supported the Argentine Mothers. It was also the period during which Total Design had to face the beginning of a total new approach to design by young studios like Wild Plakken and Hard Werken. “Great designers, really, and wonderful colleagues too. I admired their expressive, sometimes brutal approach to projects. Fascinating. They turned everything upside down.”

1983. A retrospective show of TD’s work was to be shown in De Beyerd in Breda, called: 20 years design: Total Design. Daphne was a member of the editorial team. Kees Broos wrote the text of the catalog and dedicated a chapter to all discussions and critique TD had incited by being outspoken about their professional ideas and opinions.

Later, Loek van der Sande managed to attract huge commissions from Hong Kong (for the new headquarters of the Shanghai Banking Corporation, designed by Norman Forster) and from Paris (the identity, signposting system and interior design of Parc de la Vilette). “For Vilette several TD designers were asked to produce proposals. My husband Ben Duijvelshoff was asked to participate as well and Wim Crouwel selected his design. Just wonderful! For many years, Ben had worked for De Bijenkorf department store as their art director and their creator of store windows, so he could handle space and ingenious constructions.” In the end the Grapus designers were commissioned to create the corporate identity and TD to design the signposting system. Van der Sande and Daphne together presented TD’s design in Paris. She played a leading role in the design for the museum of contemporary art CAPC in Bordeaux, France as well. Again, it was Loek van der Sande who rode shotgun for her. “Loek was a go-getter. He knew how to enthuse people.”

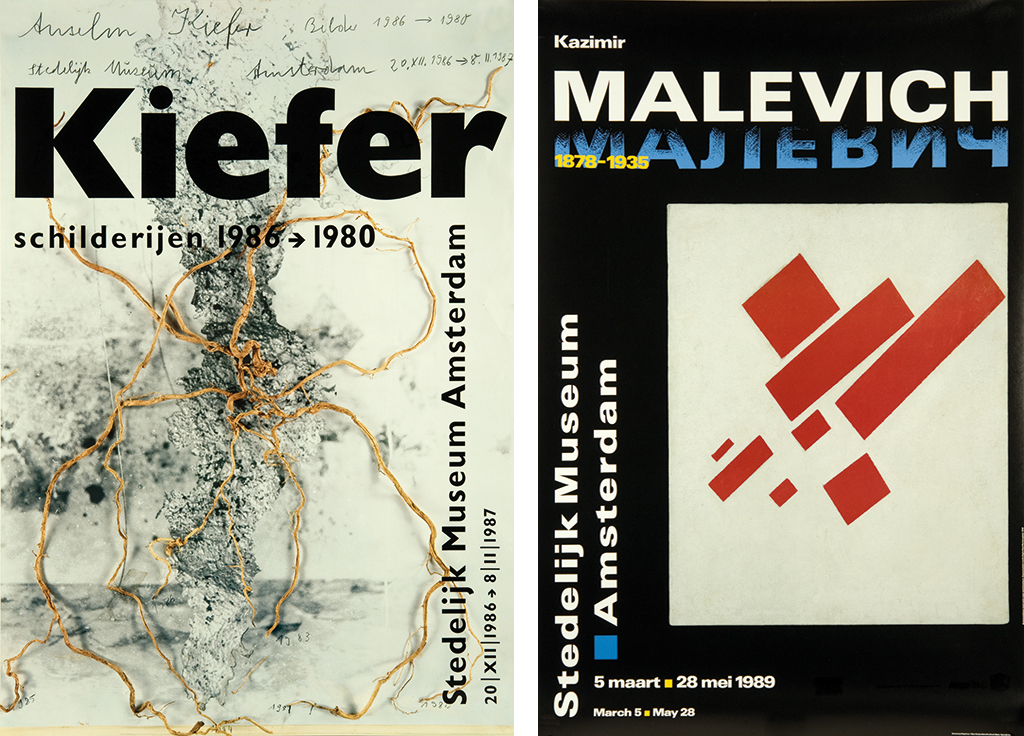

Sometime during her engagement with Museum Boijmans-van Beuningen, Daphne was asked to create a calendar to present work by Walter de Maria, including his land art project Lighting Field. No, she said: no calendar, that’s too Pirelli. The proposal she came up with was an oblong book. De Maria loved the concept. Meanwhile, Wim Beeren had moved back to Stedelijk Museum (while Wim Crouwel took over as director of Museum Boijmans-van Beuningen). Keith Haring was scheduled to have an exhibition in Amsterdam and Daphne flew to New York to visit him at his studio and discuss the design of the catalog. This (also oblong) catalog was selected as one of the Best Designed Books of 1986 by the Dutch collective for book and readership promotion, CPNB. In the same year, another book design by Daphne was selected: the catalog she designed for Anselm Kiefer. There had been a lot of discussion in the jury: “Some members of the jury were of the opinion its design was ‘excessive’ and ‘too trendy’. But all agreed a new period had begun now Wim Crouwel no longer put his mark on the graphic presentation of the Stedelijk.” Daphne would receive many more CPNB awards. For her book Industrie & vormgeving (Industry & design) she received a bronze medal from ‘Die Schönste Bücher der Welt’ (Leipzig, 1986).

When Total Design decided to leave their Herengracht studio, Daphne was involved with the search for a new location. In Van Diemenstraat they found an old warehouse that appeared suitable and architect Koen van Velsen was commissioned to create the ideal workspace. “His proposals went in a direction I didn’t agree with. The designers would be located in the middle of a large space without any windows and they had to go up some stairs to get fresh air. Meanwhile the directors were to get great rooms with a wide view of the IJ River. My choice would have been different, more social.” But as a deputy-director Daphne held less power than the other directors, who made all the important decisions. She aspired to a full directorship, but when her request was refused she decided to leave TD. “Sans rancune. It was time to go.”

In 1987, Ben Duijvelshoff and Daphne together started a new studio in a new annex at their home in Vreeland. No few of her clients switched, too: Wim Beeren (Stedelijk Museum), Jan Lodeizen (Openbaar Kunstbezit) and the Peter Stuyvesant Foundation preferred to work with Daphne as their designer.

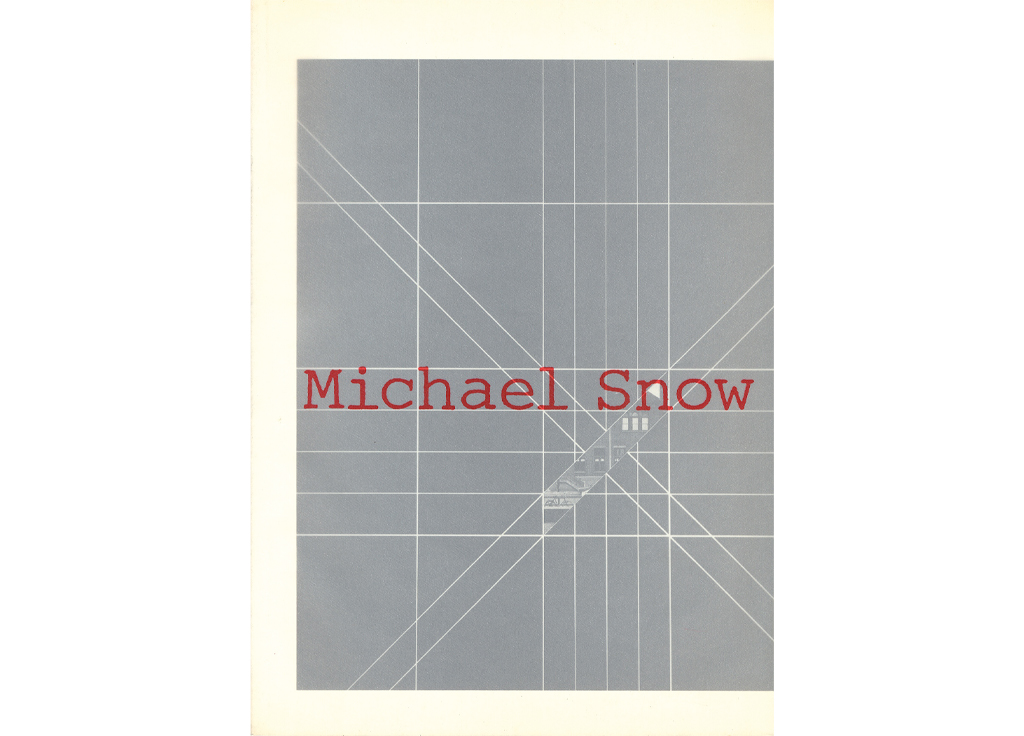

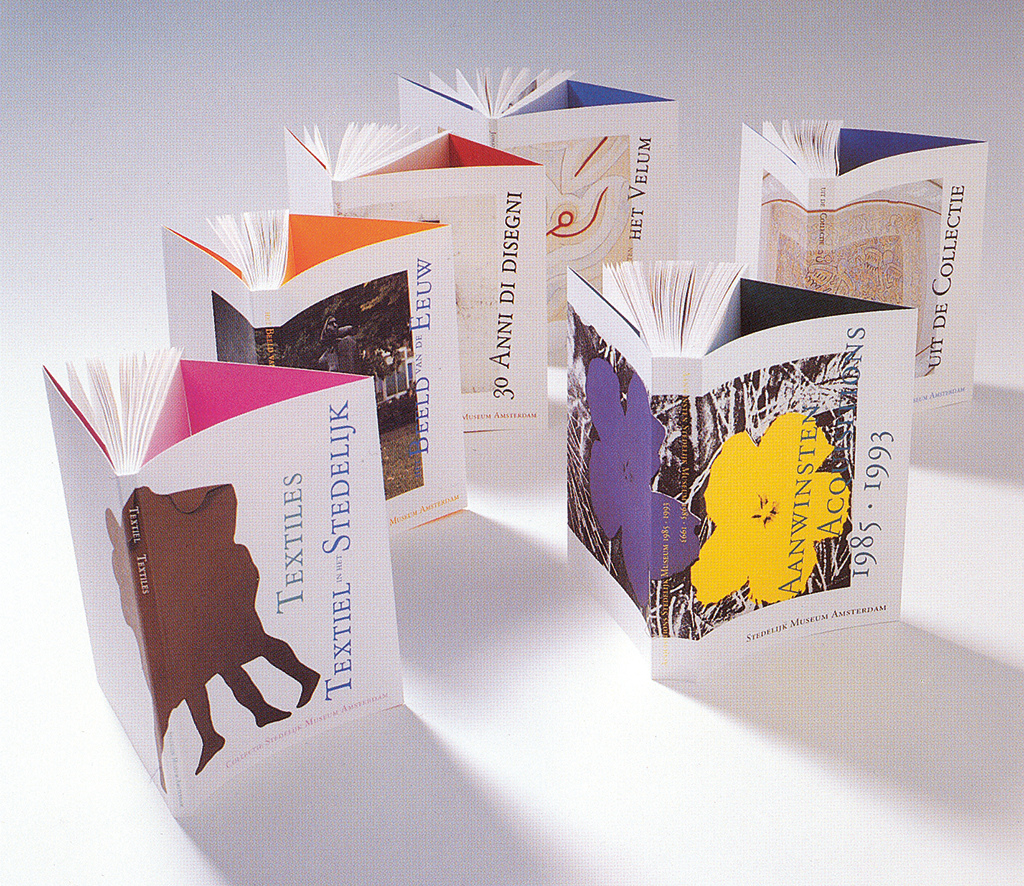

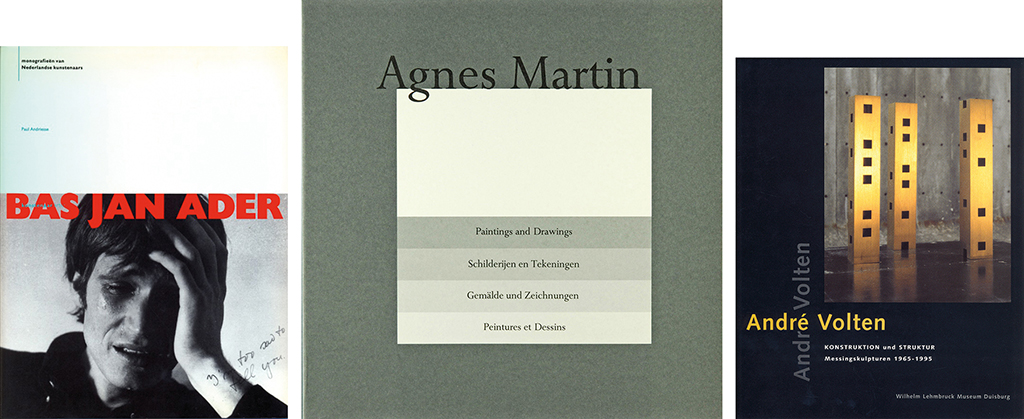

When in 1988 Openbaar Kunstbezit became a part of Sdu (government printing office), Daphne was commissioned to continue the design of a series of monographs of Dutch artists, of which the first three issues had been designed under her supervision at TD. On request of Sdu she switched from using cool grey covers to colorful cover designs including an art piece of the artist. Also in 1988, Daphne was invited to present her recent creative work in an exhibition at Museum Waterland in Purmerend. In a review of the exhibition a critic referred to the functionalism so recognizable in everything designed by Total Design, but also signaled that Daphne was not too strict a designer. What stood out, the critic wrote, was the strong bond with her artist subjects.

In 1991, in an interview, Daphne (then president of the section of individual designers associated with bNO, as the professional organization for graphic designers was then named) expressed her strong opinion about the position of free-lance designers. bNO had published a survey of their economic position, executed by the University of Amsterdam. “Everyone has to learn by experience. Everyone makes mistakes, commercially and financially. Also if you work for an agency, you are sure to fall flat on your face at some point and you learn your lesson. However, if you are employed by an agency, you are protected. On your own, you have to carry the financial burden all by yourself.”

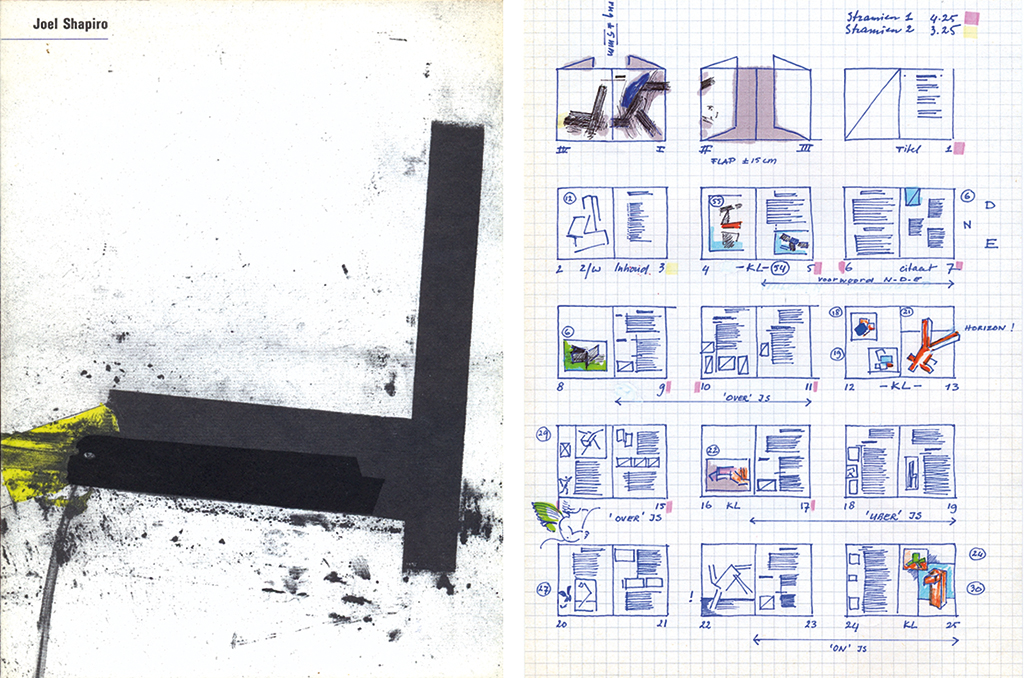

Ben Duijvelshoff assisted Daphne with her work for Stedelijk Museum. For example, they went to Leningrad to prepare for the big Malevich catalog. Ben’s design approach differed much from Daphne’s. He would come forward with an often brilliant solution only at the last moment. Meanwhile, Daphne entered the design process well-prepared, calculated how many pages would be needed and sketched out the whole lay-out. Working together in one space was not a good idea, so they made separate studio rooms in their Vreeland annex. Ben passed away in 2002.

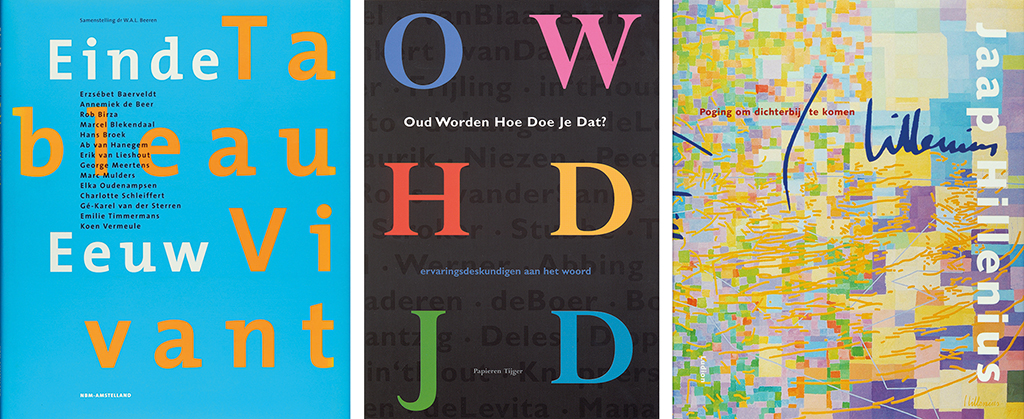

During her period as a self-employed designer, some of Daphne’s clients were: Prins Bernhard Foundation; Noordbrabants Museum and Haags Gemeentemuseum; publishers such as Gottmer, Meulenhoff, and Waanders; design group Trude Hooykaas; Art to Artisans foundation, Beeldrijk, and the foundation stimulating Dutch cultural broadcasting productions. She enjoyed her freedom during the twenty years that followed her involvement with Total Design: “Looking at my oeuvre I see a cacophony of colors. I am constantly playing with color. After TD, my work became more exuberant and liberated.”

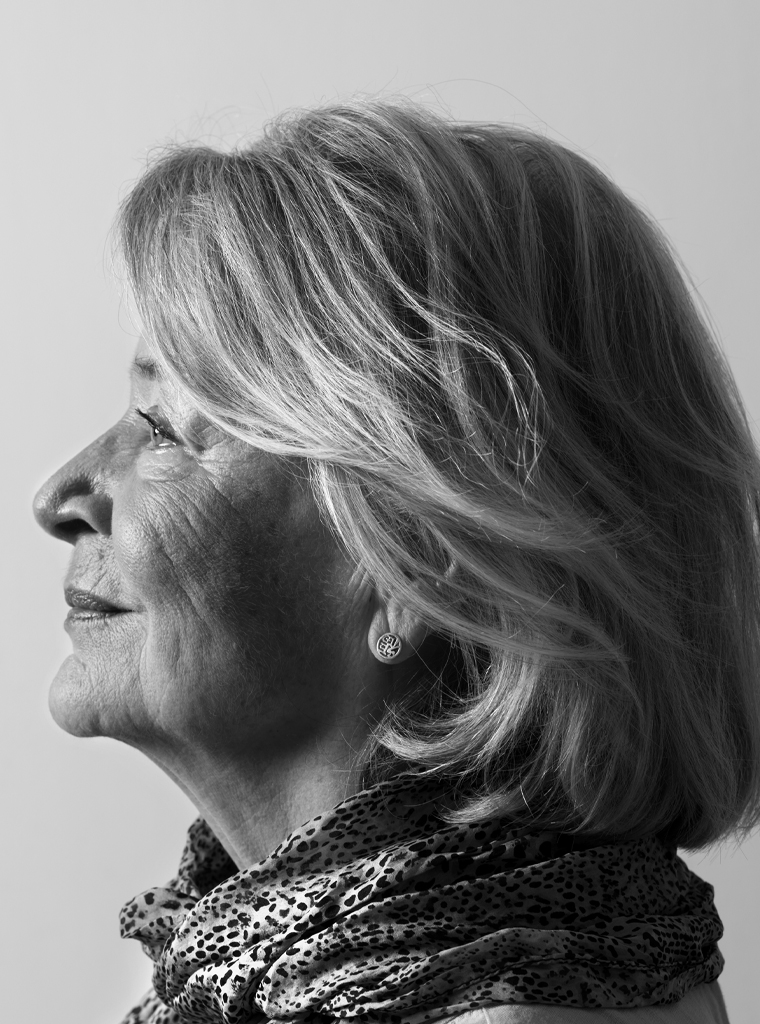

Daphne van Peski

born on 17 September 1942, Genève (Switzerland)

died on 31 July 2020, Den Haag

Author of the original text: Titus Yocarini, January, 2013

Translation and editing in English: Ton Haak

Final editing: Sybrand Zijlstra

Portrait photo: Aatjan Renders